The Lincoln Motion Picture Company: Pioneers of Black Cinema

This article is from the summer 2021 issue of CCAHA's Art-i-facts newsletter. Click here or use the link at the bottom of the page to view a PDF of this issue.

D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation launched the mainstream Hollywood film industry in 1915. Simultaneously, Griffith’s viciously racist film sparked an epic century-long struggle for African Americans to establish an equitable and authentic voice and presence in American film. Over the years, CCAHA paper and photograph conservators have worked on more than one hundred items that illuminate this history. In 2019, CCAHA received a singularly exciting project for the treatment of movie posters, lobby cards, press kits, and other ephemera from the early years of movie history. The smallest item in the collection could arguably be viewed as the most foundational. It was a stock certificate for 100 shares in the Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1916-23), the first formally incorporated Black-owned company established to film Black stories for Black audiences. It is a testament to the vision of the very earliest Black film pioneers. Their stories are largely forgotten today, with their businesses long-closed and most of their films lost. But if this was failure, it was heroic failure, probably inevitable in the face of massive social, legal, and economic obstacles. Their vision is still being fought for today, more than a century later.

Shortly after the development of motion picture film and projection in the late 1800s, filmmakers began to look for ways to effectively tell stories and market them to the public. Quickly overcoming their initial reputation as a novelty item, short films running up to twenty minutes in length soon demonstrated that the new medium could be an engine for generating income, potentially a lot of money. In 1915, film director D.W. Griffith created the template for Hollywood fame and fortune with his nearly 3 ½ hour epic The Birth of a Nation. Crowds responded, money poured in, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson praised Griffith’s achievement, and Hollywood tasted real power for the first time.

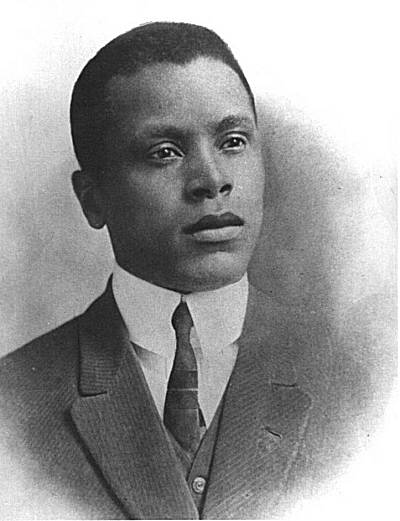

Noble Johnson, his brother George P. Johnson, Clarence Brooks, Oscar Micheaux (right), and others watched in dismay as The Birth of a Nation juggernaut smashed box office attendance records across the nation. They understood that D.W. Griffith’s blockbuster was toxic to its core, awash in racist assumptions and historical inaccuracies. It openly promoted the vigilante terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan, a movement that had been losing power and influence in recent years. Within months of the release of The Birth of the Nation, the Klan was reinvigorated and openly spreading hate and terror again.

Noble Johnson, his brother George P. Johnson, Clarence Brooks, Oscar Micheaux (right), and others watched in dismay as The Birth of a Nation juggernaut smashed box office attendance records across the nation. They understood that D.W. Griffith’s blockbuster was toxic to its core, awash in racist assumptions and historical inaccuracies. It openly promoted the vigilante terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan, a movement that had been losing power and influence in recent years. Within months of the release of The Birth of the Nation, the Klan was reinvigorated and openly spreading hate and terror again.

Ambitious Black men intrigued by the potential of film, the Johnson brothers (Noble and George), Brooks, and Micheaux, along with a handful of others, decided that the best way to respond to a film was with film. They grasped the inherent power of the medium and aimed to harness it. In 1916, Noble and George Johnson, actor Clarence Brooks, and a local pharmacist named James T. Smith formed the Lincoln Motion Picture Company and began making movies. Their first three movies—The Realization of a Negro’s Ambition, The Trooper of Troop K, and The Law of Nature—were well received… in the limited number of theaters that agreed to show them.

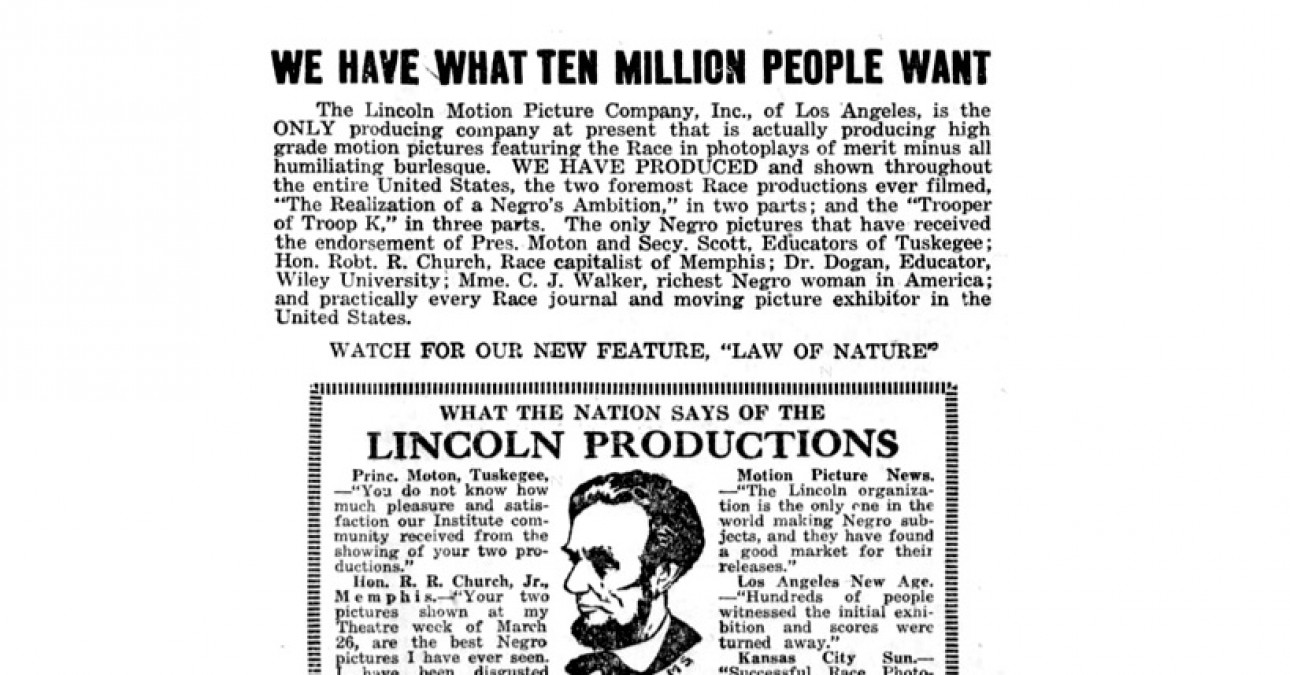

In 1917, the influential Black newspaper Chicago Defender reported:

“There is only one race film company worthy of the name, that is the Lincoln Motion Picture Co., Inc., of Los Angeles, Cal. It is distinctly a Racial proposition, owned, operated and financed by our people only—not a white person even being allowed to own one share of stock.”

This was the dream: Black people making Black movies presenting Black stories. The stock certificate treated by CCAHA Paper Conservator Chloe Houseman preserves the early memory of that idealistic vision of a dream that would—for many decades following—be long deferred.

• The dream was deferred because so-called “Race Films” were intended primarily for segregated theaters and there were approximately 300 of these Black theaters in the US as compared with 20,000 white theaters. As an unwritten rule, the white theaters did not show Race Films. Therefore, with only 2% of theaters available to show their movies, only the most cheaply produced films could have any chance of turning a profit…

• The dream was deferred because a confusing patchwork of local censors in states and cities claimed the right to demand customized editing of the reels sent to their theaters, with their choices of offending scenes eliminated. And then people complained because the movies didn’t make sense…

• The dream was deferred because the nouveau-riche mainstream Hollywood industry wanted Black actors in the background and they were willing to pay for them. Noble Johnson was a case in point. He starred in Lincoln Film’s early productions and quickly became very popular. To bring in more money, he performed in mainstream Hollywood studio productions, playing roles like Cannibal Chief, Slave Broker, and Nubian Servant. Then Universal Studios requested that he sign a contract with a non-competition clause, effectively barring him from working with Lincoln, the studio he founded. Universal promised a good, steady income; Lincoln’s future was financially uncertain. Noble Johnson signed the contract in 1918.

While this collection of film memorabilia was being treated at CCAHA, Senior Conservation Assistant Jillian Herrick Wilcox was particularly moved by a copy of The Negro Motorist Green-Book, an annually-issued (1936 to 1966) guidebook for African-American travelers that received renewed public attention with the success of the Oscar-winning film Green Book (2018). For Jillian, the old guidebook brought back memories of the Green Book that her grandparents carried with them whenever they traveled. She has no idea what became of their copy.

Ephemeral items like the Green Book were designed for immediate use rather than long-term preservation. In most cases, they were quickly discarded. Because so few have survived, a chance encounter with a surviving pamphlet, movie poster, or lobby card can deliver an emotional jolt. For others, these items offer an unexpected glimpse of the world that our ancestors knew and experienced. In four cases, CCAHA conservators treated items associated with movies— The Crimson Skull (1922), A Prince of His Race (1926), Black Gold (1928), and Brother Martin, Servant of Jesus (1942)—where the original film is believed to be lost. In the case of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, all seven of their films are lost, except for four minutes of deteriorated film footage from their last feature film, By Right of Birth (1921).

The movie posters provide particularly thrilling windows into the past. As Jillian says, “People needed these movies. They were inspirational, something they could take pride in.” She was particularly impressed by The Flying Ace (1926), an adventure movie from the silent era that featured a heroic Black aviator, fresh from World War I and ready to take on the bad guys. “A movie like this said that you are equal,” Jilliann says. “You can fly, be an officer, you can do it.” CCAHA conservators treated the press kit for The Flying Ace, which spins creative ideas on how to promote the movie to local audiences.

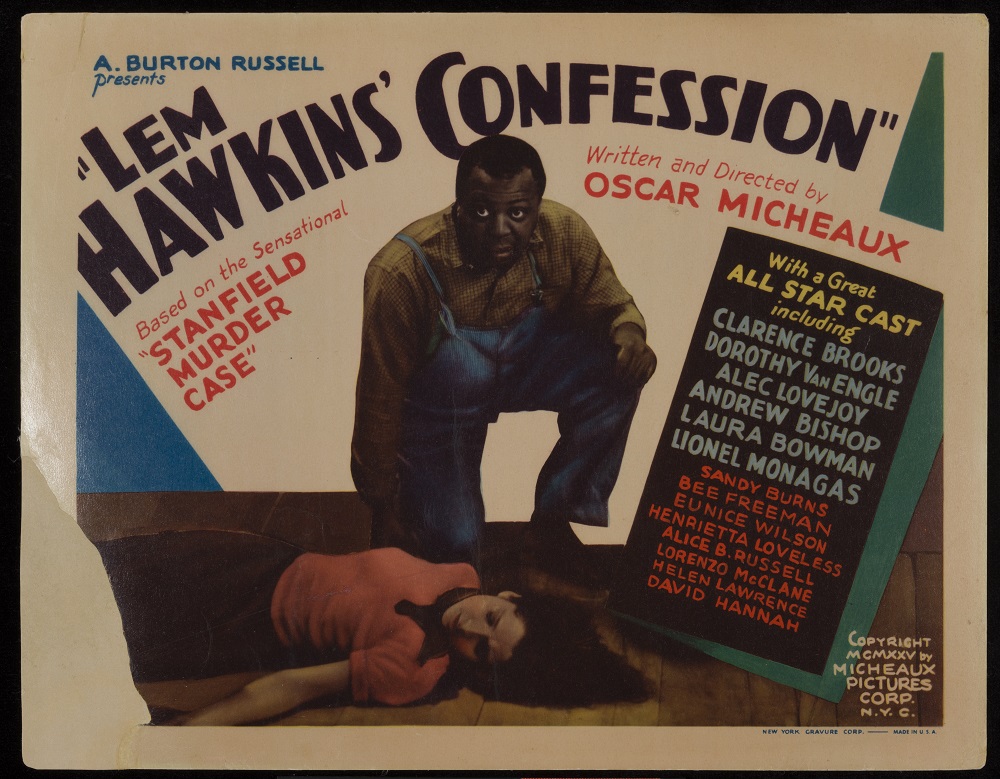

The dream of an independent successful Black-run movie studio was strong in the silent years of the 1920s but faded with the arrival of sound (requiring an investment in much more expensive equipment) and the Great Depression. Pioneer Black film director Oscar Micheaux was the only figure from the 20s who stubbornly held on to his independent status, making ambitious if low-budget movies like Lem Hawkins’ Confession (1935) and Lying Lips (1939). CCAHA conservators treated a poster for Lying Lips and three lobby cards for Lem Hawkins’ Confession. (To see more, visit the CCAHA YouTube channel to view night four of our 2020 Virtual Open House.)

After World War II, the mainstream Hollywood studios began to cultivate a handful of African-American stars, such as Dorothy Dandridge, Harry Belafonte, and Sidney Poitier, maintaining just enough mainstream opportunity to keep an independent movement from taking hold. But while the casts were sometimes reasonably integrated, the large film crews working behind the scenes remained largely white. From this period, CCAHA conservators have treated the posters of such films such as Cabin in the Sky (1943), Pinky (1949), Carmen Jones (1954), Anna Lucasta (1958), and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967). The poster for Pinky is particularly interesting, with a line bisecting Pinky’s face, one side subtly portrayed with white features and the other with Black, graphically suggesting the movie’s central theme of “passing.”

The most recent movie items treated by CCAHA conservators have come from the late 1960s and the 1970s, capturing a time when the dream of independent Black filmmaking finally returned. Acclaimed photographer and artist Gordon Parks led the way with his independent production of The Learning Tree (1969), an autobiographical look back at growing up in rural Kansas in the 1920s. While The Learning Tree failed to catch on at the box office, Parks’ follow-up film, Shaft (1971), was a big hit, cementing many of the key elements (hyper-masculine Black hero, heightened sex and violence, and funky soundtrack) of the new Blaxploitation genre. These films were usually made by mixed-race production outfits and marketed for urban African American audiences. From this period, CCAHA conservators have treated posters for The Learning Tree, Black Caesar (1973), Coffy (1973), Isaac Hayes: The Black Moses of Soul (1973), and Cooley High (1975). The poster for Isaac Hayes: The Black Moses of Soul (1973) memorably captures this moment in time, with Hayes looking like the coolest of superheroes, nearly fifty years before Black Panther.

AUTHOR’S POSTSCRIPT AND CONFESSION

As one of the so-called “monster kids” who grew up in the 60s infatuated with the old “creature feature” horror movies regularly shown on TV, I’ve always felt like I’ve known all about Noble Johnson. He was the Skull Island Native Chief who proclaims “Ana Sabi Kong!” (rough translation: “She is the bride of Kong”) in King Kong (1933), and Boris Karloff’s sinister Nubian servant in The Mummy (1932), and Bela Lugosi’s treacherous henchman in Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932). What more claim to fame could he possibly have? Learning about this largely forgotten chapter of movie history has been a revelation for me. Noble Johnson was so much more than the Native Chief in King Kong. He was a courageous visionary who leaped at the chance to respond to the insult of D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation. He was determined to publicly proclaim racial equality in a mainstream American industry forty years before the Civil Rights Movement began. Within a span of just two years, Johnson founded a company that reflected his dream; he wrote, produced, and starred in three very well-received movies that refused to pander to stereotypes; and he shared his vision with others who kept it alive despite the aggressive resistance of a system determined to keep them out. His work and the work of many other unsung heroes—who stood up against all odds to demand a strong Black presence in Hollywood—is justly celebrated by the material legacy they have left behind.

Black films matter.

—LEE PRICE

Photos, from top: A clipping from The Kansas City Sun, Kansas City, Missouri, May 26, 1917; a portrait of director Oscar Micheaux; an after-treatment reference photograph of a lobby card for the Oscar Micheaux film Lem Hawkins' Confession.

References: Oscar Micheaux & His Circle: African American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era; Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser, Editors and Curators; Indiana University Press, 2016. // Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only: The Life of America’s First Black Filmmaker by Patrick McGilligan; Harper Perennial, 2007. // Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance by Aberjhani and Sandra L. West; Checkmark Books, 2003 // Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity by Jacqueline Najuma Stewart; University of California Press, 2005