Treatment FOCUS: Fraktur

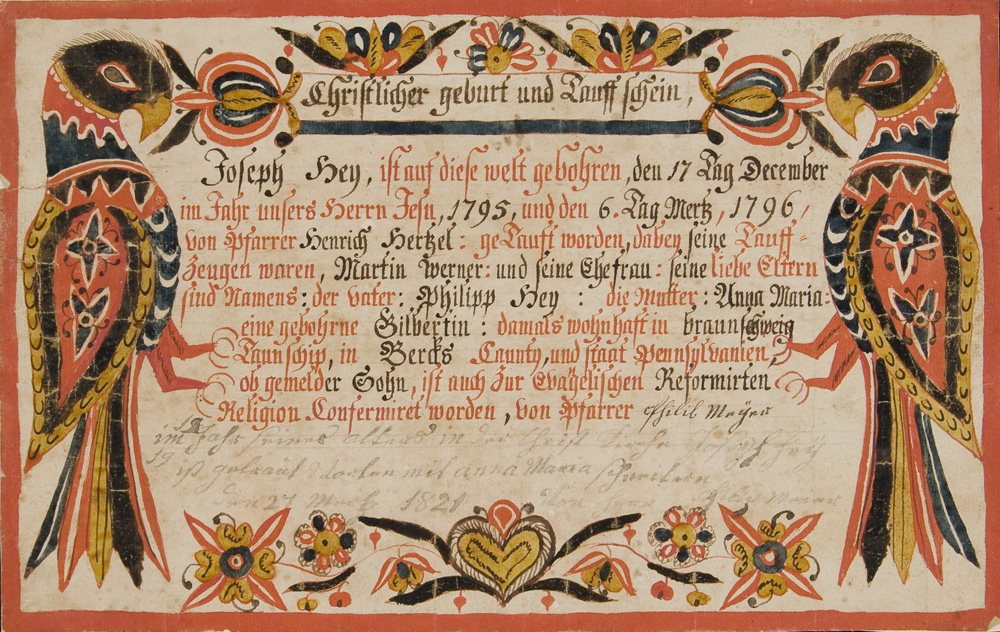

German-speaking immigrants who settled in Pennsylvania in the 18th and 19th centuries documented their religious beliefs, as well as important events in their personal lives, through decorated manuscripts called fraktur. In each, colorful images of flowers, animals, and religious scenes surround text written or printed in intricate Fraktur script or German cursive. Today, scholars study fraktur to learn about family life and religious, political, and business practices in these Pennsylvania German communities, while admirers treasure them as unique American folk art.

A birth and baptism certificate in watercolor and graphite on laid paper, which exhibited moderate surface dirt, foxing, and discoloration

The Philip and Muriel Berman Museum of Art at Ursinus College holds a collection of nearly 130 fraktur. These include birth and baptismal certificates, confirmation certificates, marriage certificates, religious texts, and memorial pieces from communities of various church denominations, such as Mennonite, Amish, Lutheran, Reformed, and Moravian. The collection contains freehand fraktur by at least 30 artists who practiced during fraktur’s Golden Age from 1790 to 1830 (by the mid-1800s, the tradition had begun to disappear, in part because municipally-run schools replaced traditional schools whose German-speaking teachers had taught and maintained the fraktur practice). The collection also features examples of machine-printed fraktur, which artists often personalized for clients with hand-coloring and decorations.

One of Berman Museum Collection Manager Julie Choma’s favorite fraktur, a birth and baptism certificate, c. 1813, drawn freehand in watercolor and ink and attributed to Martin Brechall (c. 1757-1831)

The Berman Museum recently selected 32 fraktur to receive treatment at CCAHA through a Save America’s Treasures grant. Collections Manager Julie Choma chose these fraktur partly for their historic and artistic value; some come from Ephrata Cloister, a leader in early American printing, while others are freehand works by major fraktur artists. She also based her decision on a collection survey conducted by CCAHA in 2008, with funding from the Pennsylvania Historical & Museum Commission. CCAHA conservators found that iron gall ink (which artists sometimes used alongside watercolors, graphite, and other inks) presented the primary threat to the collection, as the ink becomes acidic with age and weakens paper supports, leading to losses in paper and text. Some watercolor elements were faded or insecurely attached to the paper supports, and the manuscripts exhibited occasional creases, tears, losses, and staining.

CCAHA conservators will surface clean each fraktur with grated and solid vinyl eraser, consolidate media and glazes, and remove adhesive and accretions before washing some documents and reducing stains. Next, they will mend and fill losses and humidify and flatten each document. Finally, they will hinge each fraktur to an alkaline mat and return the collection to the Berman Museum, which will store it in flat file units in a new works-on-paper seminar room. The room provides a secure environment in which researchers and students will be able to study the collection, and its wall space allows for display of the fraktur (or facsimiles) for all visitors to enjoy. Choma notes that the Museum always has requests for the fraktur, not only for family and local history research but for viewings by individuals who find them visually stunning. “It’s fun to have objects that people respond to for so many reasons,” she said. “We were thrilled to receive the grant to conserve them.”