The Amistad Research Center’s Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture by Jacob Lawrence

Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) was a Harlem Renaissance painter whose self-described style of "dynamic cubism" brought to life everyday scenes and illustrated some of the major narratives of Black history. In 1938, at just 21 years old, Lawrence painted a series spotlighting Toussaint L'Ouverture, the former French general and Black revolutionary who led the revolt of enslaved people that established the nation of Haiti. The series includes depictions of key moments in the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804).

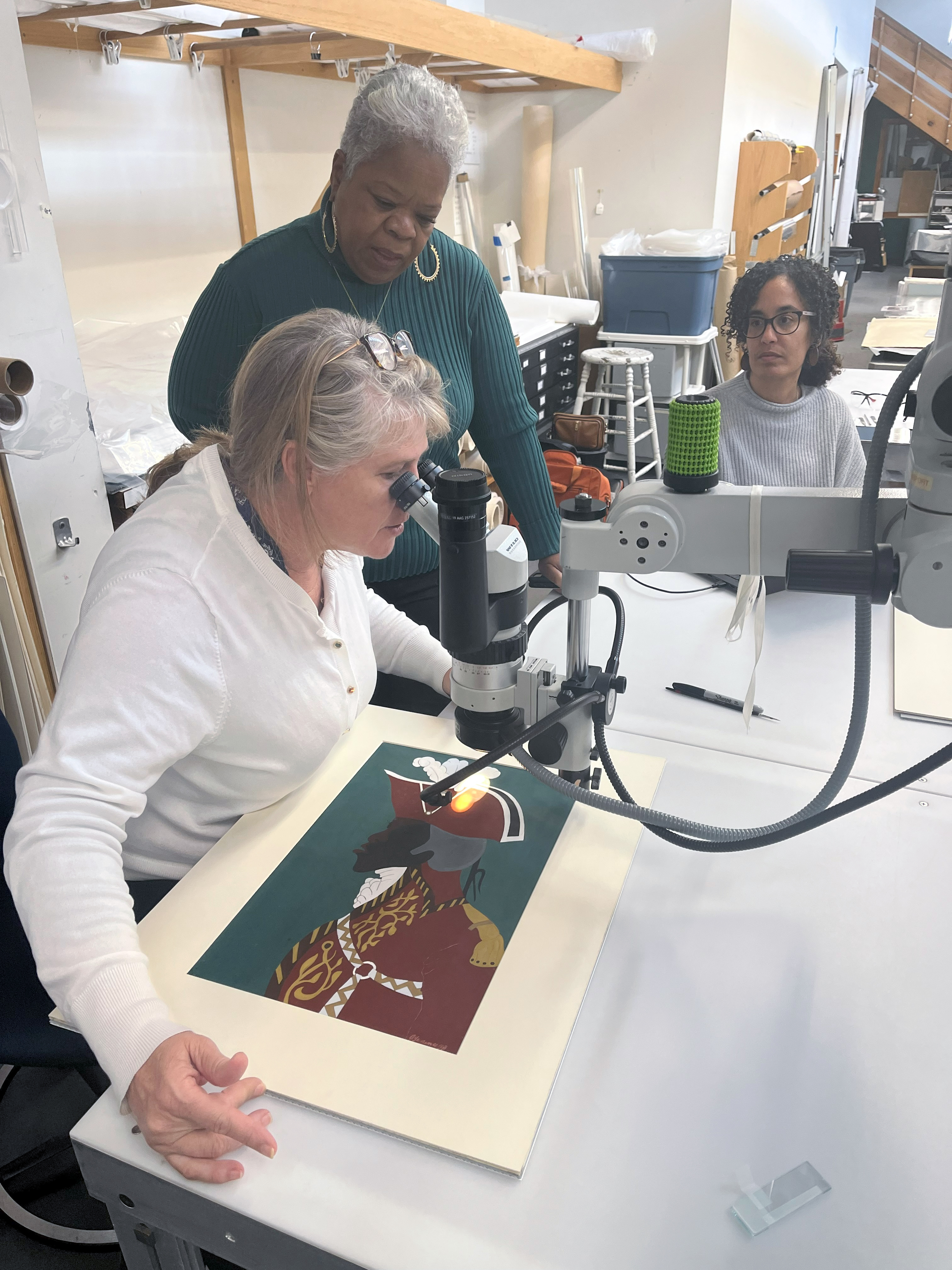

Lawrence's paintings of L'Ouverture now belong to the Amistad Research Center in New Orleans. The Amistad's Executive Director, Kathe Hambrick, recently traveled to CCAHA to spend a day overseeing research into the collection's condition. She was met there by scientists Joy Mazurek and Ashley Freeman from the Getty Conservation Institute in Los Angeles, who performed onsite analysis and collected samples for further research at the Getty facilities.

"I'm here to observe," Kathe says, "to better understand the process. It's very educational to me, as I may have to explain it to my stakeholders. Also, I think this is just a great collaboration between the Getty, the Amistad, CCAHA, and the Terra Foundation for American Art, who are funding CCAHA's work."

The paintings on the table that day looked vibrant and kinetic, but microscopic problems on their surfaces threaten their longevity.

"There were concerns about haziness showing up in some dark areas [of the paintings]," says CCAHA Senior Paper Conservator Heather Hendry. “It sounded like a problem CCAHA had treated before.”

CCAHA staff saw a similar issue with Lawrence's early 1980s series examining the impact of the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima, from the collections of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA). That haziness was believed to be caused by fixative and was treated with solvents.

But there can be many causes of the same visual effect.

“There was also a conservator at the Phillips Collection [in Washington, D.C.] who dealt with haziness on a different Jacob Lawrence series,” Heather adds. “The Getty did analysis and identified it as probably efflorescence from an egg tempera medium. The museum’s conservator, Elizabeth Steele, was able to remove it mechanically."

"Now, in this case, we're trying to identify what's causing it. Is it a fixative applied over the paint? Is it something efflorescing from the original medium?"

Mazurek and Freeman spent two days in New Orleans looking at the other half of the collection before traveling to CCAHA's lab in Philadelphia.

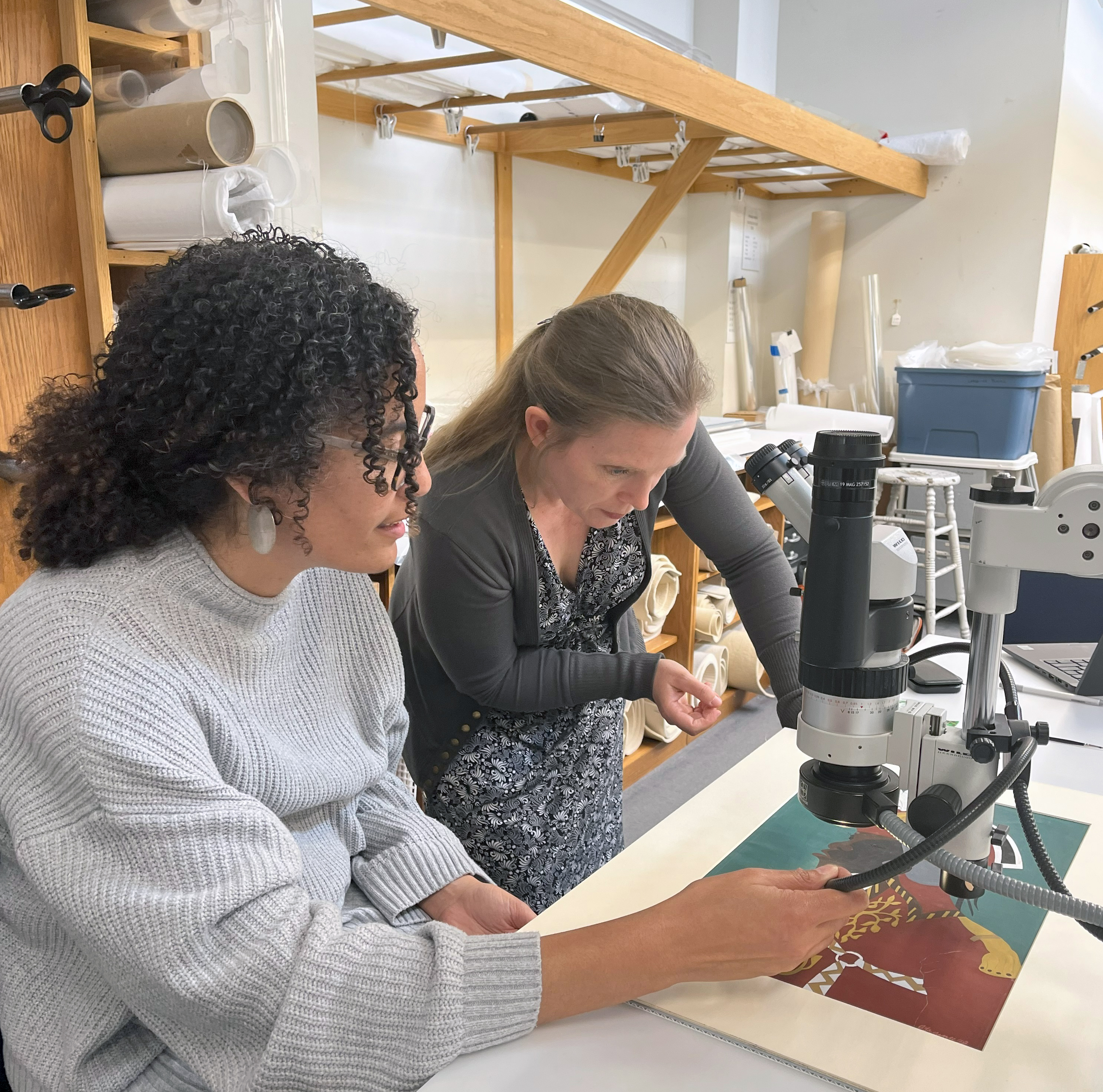

"What we're finding more is loss," Heather explains. "When you examine the paintings under the microscope, it looks like losses in the paint film."

"What we're doing now is sampling in very discrete locations," Heather continues. "So, if we find a tear where there's already a loss, we can get a little sample that they can take back to analyze and use to determine how we're going to address this. If it's all paint loss, that's almost something we can't address, because we're certainly not going to overpaint on his paintings. But we will be doing some corrections.

That could involve minor inpainting around areas like tears. Heather points to such an area and says, "We could improve that... but we wouldn't paint every grass blade."

There's also the interesting possibility of the inconsistent tone being the artist's intent.

"There's some question about whether he applied the paint very thinly. Was it a thin wash where it always looked a little lighter, and not a solid black? Or has this happened over time due to the collection's irregular history, irregular care in the past?"

"Part of what Amistad is doing now is professionalizing the care of these paintings," Heather adds. "They're first going to be conserved, then we're going to house them in sealed packages. There will be some major exhibitions, but Amistad is talking about storing them for the long term in an off-site art vault with very controlled conditions."

The Getty scientists, CCAHA staff members, and Kathe take turns looking at the paintings through the microscope, discussing the technicalities of potential treatment, but also simply admiring the impressive artwork in front of them.

"Jacob Lawrence was certainly one of the masters of American art," Kathe points out. "The world is very excited to see these paintings, and we look forward to being part of preparing them for exhibit."

The paintings will show in three exhibits — including France and the East Coast and West Coast in the U.S. — at the end of the conservation work.

"There's an interest, considering what's going on in Haiti today,” Kathe says. “I think, historically, the timing is going to be perfect."

From top: Detail of a portrait of Toussaint L'Ouverture by Jacob Lawrence, from the collections of the Amistad Research Center; from left, Joy Mazurek, Kathe Hambrick, and Ashley Freeman examine the portrait; Amistad's Kathe Hambrick takes a closer look through the microscope; detail of another painting in the series depicting a scene from the Haitian Revolution; the Getty's Ashley Freeman and CCAHA's Heather Hendry.