Chambersburg 1864: A Classic Civil War Photograph

Because of the constraints of photography in the art form’s early days, photographs of the Civil War tended to be either posed portraits, camp scenes, or—most haunting of all—images of a battle’s aftermath. Taken days or even weeks after the violent events had passed into history, the aftermath images depict tragedy recollected in tranquility.

Sometime in August 1864, Charles L. Lochman of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, drove a wagonload of photographic equipment 30 miles southwest to Chambersburg. He found a city in ruins. On July 30, 1864, Confederate troops under the command of General John McCausland had set fires throughout downtown Chambersburg, burning the center of town to the ground. It was the third and worst of three Confederate incursions into Chambersburg during the war, and left approximately 3,000 people destitute, their homes and businesses destroyed.

Lochman captured the devastation through his lenses. In order to accommodate the vast scope of the damage, he opted to create a panoramic photograph. Usually at least twice as wide as it is high, a panoramic image is ideal for depicting a broad landscape, either natural or urban. Compared to a standard photograph, it conveys an almost epic vision—not what the eye sees when looking straight ahead, but the world as perceived when you scan the horizon.

From the roof of the Chambersburg Market House on Second and Queen Streets, Lochman framed a view that looked down upon the western side of town, which had sustained the greatest damage. Using his heavy and cumbersome equipment, he took three glass plate negative images, pivoting the camera to a new position for each shot, carefully allowing for image overlap. After making three albumen prints from the negatives, Lochman cut and pasted the pieces together to create a final panoramic image. The resulting photograph, labeled “View of the Ruins of Chambersburg,” is nearly two feet in length and 7¾ inches high.

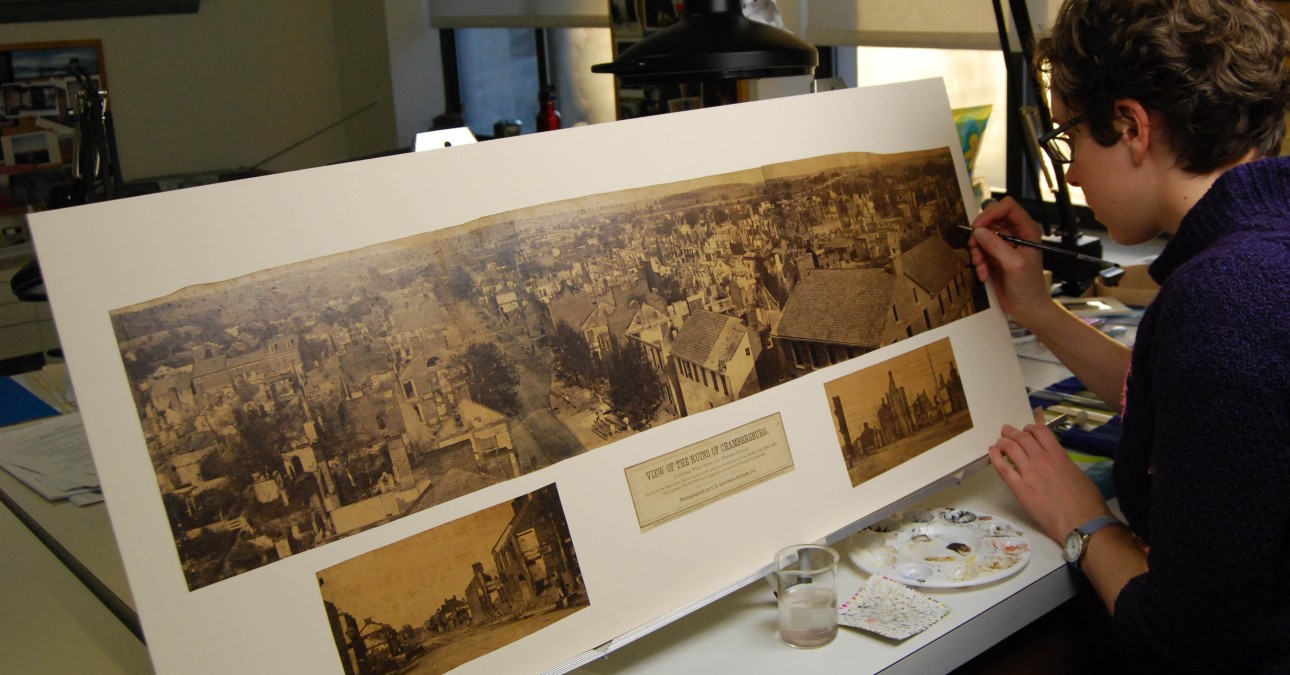

Keister lining the document.

Today, this powerful photographic image resides in the collections of the Pennsylvania State Archives. In late 2013, Paper & Photograph Conservator Jessica Keister was privileged to treat the photograph at CCAHA. When it arrived at CCAHA, it was discolored and had a thick layer of surface grime.

While aging is natural for a 150-year-old image, this particular albumen photograph additionally suffered from a heavy application of a shellac-based varnish. The yellowing of the varnish made the natural shifts in the tonality of the albumen prints more severe. Keister successfully removed the varnish with a series of solvent baths, reducing the overall discoloration to a considerable degree. The results of the treatment brought out details that were previously obscured by the discolored varnish.

Even with this increased clarity, you have to look closely and take some time with the image to begin to comprehend its mute witness to history. At first, some of the buildings on Queen Street, the main avenue that bisects the center of the image, appear to be undamaged, until you notice that they are just façades, with the roofs burnt away and nothing left inside. Behind these structures are ruins in even worse shape, sometimes consisting only of free-standing single walls. Second-floor windows that would have once looked into bedrooms now gaze out on open space. And in the distance, offering an ironic counterpoint, lies a bucolic Pennsylvania landscape on what appears to be a quiet, clear summer day.

Two smaller, street-level photographs were pasted beneath the main panoramic image on the paperboard support of the artifact from the Pennsylvania State Archives. At this level, you can see the rubble piled along the sidewalks. The photograph on the left depicts a close view of the center of town at the flagpole, including the remains of the Golden Lamb Hotel, the oldest stone structure in town before it was consumed by fire.

The photograph on the right is the only one to capture human life amid the wreckage. The tiny figure of a man can be seen in the left foreground, the precarious façade of a building rising high above him.

In the years that followed, the people of Chambersburg rebuilt their town. Two years later, the Pennsylvania Legislature passed an act that compensated the citizens who lost property on the day their town burned. The resulting inventories provide a rich historical view of the world of Chambersburg before disaster occurred. The imaginative historian can reconstruct a world that vanished in a day. Behind the empty windows in the photographs, there were rooms filled with tables, chairs, cupboards, wardrobes, washstands, bedsteads, and lamps; kitchens teeming with sugar, syrup, coffee, chocolate, spices, and soda; and people moving ahead with their lives, attired in the period’s dresses, bonnets, aprons, trousers, suspenders, shoes, stockings, shawls, and coats.

On July 30, 1864, that world was reduced to ash and rubble. Charles L. Lochman’s panoramic photograph eloquently captures the loss that inevitably accompanies war’s aftermath.

The conserved photograph is on display at the Burning of Chambersburg Exhibit at the State Museum of Pennsylvania through June 2014.