Digital Imaging: Many Options, Many Uses

Like many archival repositories, the Moravian Archives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, opens its reading room to those wishing to study its holdings. Scholars researching papers, family historians investigating their genealogy, and church leaders seeking information on their congregations: all are invited to visit the Archives, which preserves the records of the Moravian Church in America, Northern Province.

Although the Archives restricts researchers as little as possible, it cannot grant access to delicate artifacts that disintegrate at the slightest touch—as is the case with the second volume of Bishop Matthaeus G. Hehl’s diary. Hehl served as pastor to the Moravian community of Lititz, Pennsylvania, during the American Revolution. His manuscript provides a firsthand account of the tumultuous years between 1771 and 1784, when war disrupted daily life, and other Lancaster County residents sometimes mistook the Moravians’ pacifism for loyalty to the British Empire.

To reconcile the need to provide access to this unique artifact with the responsibility to protect it, the Archives brought the volume to CCAHA. In addition to conservation treatment, CCAHA recommended digital imaging.

CCAHA established its imaging studio in 2008 with support from The McLean Contributionship, The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, and The Barra Foundation. At that time, the studio’s main responsibility was to document the conservation process for treatment projects using high quality TIFF files, processed from raw data digitally captured by a camera or flatbed scanner.

Today, Manager of Digital Imaging Andrew Pinkham and technicians Keith Jameson and Tamara Talansky produce much more than before- and after-treatment images. They can create digital archives recording every leaf of a book, photograph in an album, or item in a collection, treated or not. Individuals might use these digital collections to organize their personal histories or share information with family members. Collecting institutions add the images to their websites and printed promotional materials, send them to media outlets to accompany articles, and—perhaps most importantly—offer them to researchers.

For the Moravian Archives’ Hehl diary, Pinkham suggested digitization of the entire volume, resulting in TIFF, JPEG, and PDF files of each page. Completed with funding from Dr. Scott Paul Gordon, a Lititz scholar and Lehigh University professor, this image library will allow the Archives’ visitors to study the diary’s contents without jeopardizing the fragile original, which will remain susceptible to damage from handling, even after treatment.

The use of facsimiles, high resolution copies produced from digital images of objects, can also protect originals from handling and exposure. Reference facsimiles are the most basic option. Because only minimal color adjustments are made to the digital image before a reference facsimile is printed, the print’s colors will not exactly match those of the object. Although not appropriate for exhibition, a reference facsimile provides readers with the same needed information as an original letter, journal, or manuscript.

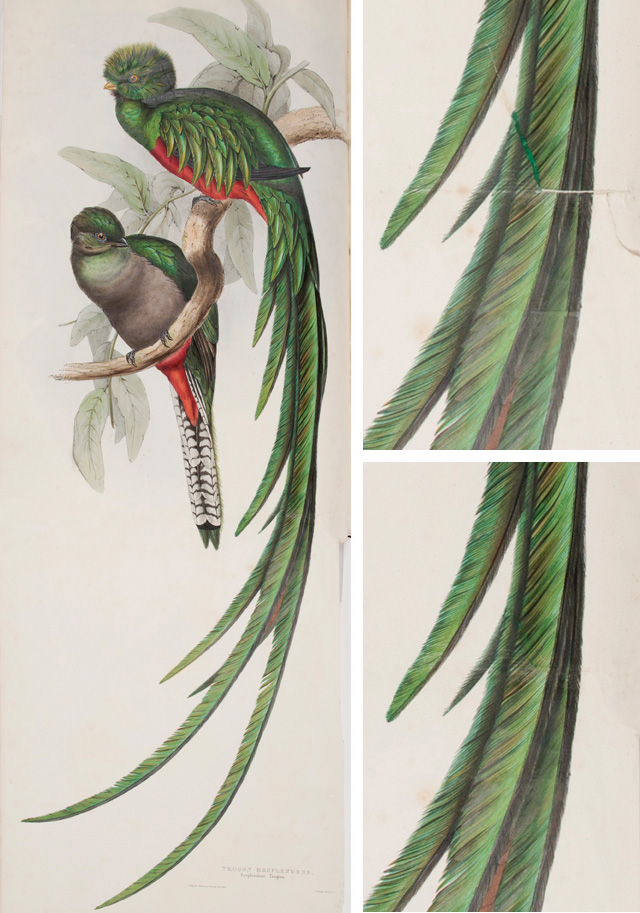

A plate from John Gould’s 1838 A Monograph of the Trogonidae, or Family of Trogons, digitally restored at CCAHA’s digital imaging studio.

Exhibition-quality facsimiles require a few more steps. After comparing an initial print to the original object, Pinkham and Jameson return to the computer to make further color corrections to the digital image. With each adjustment, they create a small test print for comparison. Color matching can be tricky— factors such as ink behavior and printer age can cause variations in color between the digital image, the print, and the original—so multiple tests are necessary. Once the color is correct, they print a full-size copy almost indistinguishable from the original.

When displayed in place of the original, an exhibition-quality facsimile helps to limit the artifact’s exposure to light. It also offers other benefits, as client John Lombard discovered last year. Lombard wanted to give each of his grandchildren a copy of 1951 Packard, a watercolor he painted when he was 16 years old and an art major at La Salle College High School in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. After treating the original—surface cleaning it, reducing a disfiguring stain, and mending tears—CCAHA produced 23 exhibition-quality facsimiles.

Because Lombard’s watercolor received treatment, facsimile production did not include digital restoration work. But in other cases, such as when it is impossible to safely treat an object, CCAHA’s imaging studio uses Adobe Photoshop to reduce stains, mend tears, reverse fading, and remedy other imperfections in the digital version. The owner’s wants and needs determine the changes, and the result can be printed as a facsimile, saved as digital files, or both.

Digital restoration helped Awbury Arboretum in Philadelphia when it needed a legible copy of a historic bird list. Several years after five Quaker women joined their properties in 1916 to create the Arboretum, someone, perhaps a family member, started a list describing the birds that migrated through it each season. Almost a century later, discoloration, stains, smudges, and fading ink left the list practically unreadable, but it appeared to reference species no longer seen in Philadelphia—and Awbury, which still welcomes birders on its 55- acre property, wanted to know more.

Through Restoring Ideals, a Philadelphia-wide, conservation-themed project funded by The Barra Foundation and organized by Temple Contemporary, CCAHA’s imaging studio digitally captured the two documents that compose the list. Jameson then reduced the appearance of stains in the images and enhanced the text by increasing contrast. Awbury’s visitors can now read the full-size facsimiles, printed from the restored images and placed into window mats, while alkaline paperboard folders store the original documents, protecting them from further damage.