A Happy Pair

Books are often no match for the rigors of childhood play, so it comes as no surprise that children’s literature poses unique challenges to conservators. Rogue marginal and interlinear additions need to be excised, torn pages repaired, and all manner of cuts and scrapes mended. These days, many children’s books are built to withstand a healthy amount of play, from infants’ board books to laminated pages. At the turn of the twentieth century, however, children’s literature was far less hardy. In a recent project at CCAHA, conservators faced one of the most common problems associated with children’s literature: a weakened binding.

A Happy Pair was published in 1890, and featured poetry by Frederic Weatherly and illustrations by Beatrix Potter. Potter was 24 years old at the time, and sold her illustrations to a German publisher for £6. It was the first book to feature Potter’s illustrations, published a decade before the first appearance of Peter Rabbit. A Happy Pair is a fourteen-page volume featuring six illustrations of rabbits based on Potter’s own pet rabbit Benjamin Bouncer.

The book was a success and Potter’s career grew from that point forward. Hildesheimer and Faulkner, the firm that bought her illustrations for A Happy Pair, commissioned several other illustrations. Pleased with her success, Potter set out to write her own stories to illustrate. Drawing on her letters to the children of her many friends, she published The Tale of Peter Rabbit in 1901. The book was very successful and was soon followed by many other recognizable classics: The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, The Tailor of Gloucester, and more. Potter published over twenty books throughout her career.

Along with her children’s books, she published articles about natural science and was a keen advocate of environmental conservation. She had a special interest in fungi, and once entered a paper on a new theory of sporing to the Linnaean Society. Potter used the proceeds from her successful literary career to foster her interest in land conservation. She lived in the area of northwest England known as the Lake District, and became very well known for her acts of generosity and partnerships with the National Trust. Upon her death, she left the nearly the entirety of her vast land holdings across the Lake District to the National Trust; the largest gift ever left to the National Trust at that time. Along with her property, Potter left many of her original illustrations to the National Trust.

Potter’s stories were part of a new wave of children’s literature. Up until the middle of the nineteenth century, the genre had been primarily religious and moralizing. But in the 1840s, a new, whimsical, imaginative children’s literature emerged. Lewis Carroll’s fantastical stories of Alice in the upside-down Wonderland and Carlo Collodi’s stories of the puppet Pinocchio opened up the doors for a new style of playful writing for children.

This change in tone was twofold; along with new subject matter, the books contained something else: color illustrations through the process of chromolithography. John Tenniel’s portrayals of the Queen of Hearts in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Kate Greenaway’s wood-engraved images pioneered a new age of children’s illustrations. With illustrators like Randolph Caldecott and authors like Lewis Carroll leading the way, the new reign of children’s literature, unfettered by previous precedents, prospered.

Today, there are few first edition versions of Potter’s A Happy Pair extant. A private collector recently brought one of these rare editions to CCAHA. When the book arrived, the binding was in poor condition, with the spine and back board missing. The holes of the stitched binding of the spine had become enlarged and the corners worn round. The front cover was attached by a single thread. The primary binding thread appeared to be original, based on other extant copies of the books, and it was cutting into the leaves of the book. The back cover was completely missing.

In order to reinforce the binding, CCAHA Conservation Assistant Heather Godlewski removed the sewing threads from the binding. She then cleaned the surface of the pages with vulcanized rubber sponges and white vinyl erasers to clear any loose soil and embedded grime. Godlewski mended the ragged edges of the leaves and cover with acrylic-toned mulberry paper and wheat starch paste. Some of the corners of the pages were consolidated with wheat starch paste as well. The front cover spine was repaired with new acrylic-toned paper and more wheat starch paste. The new spine area was then painted with watercolors to match.

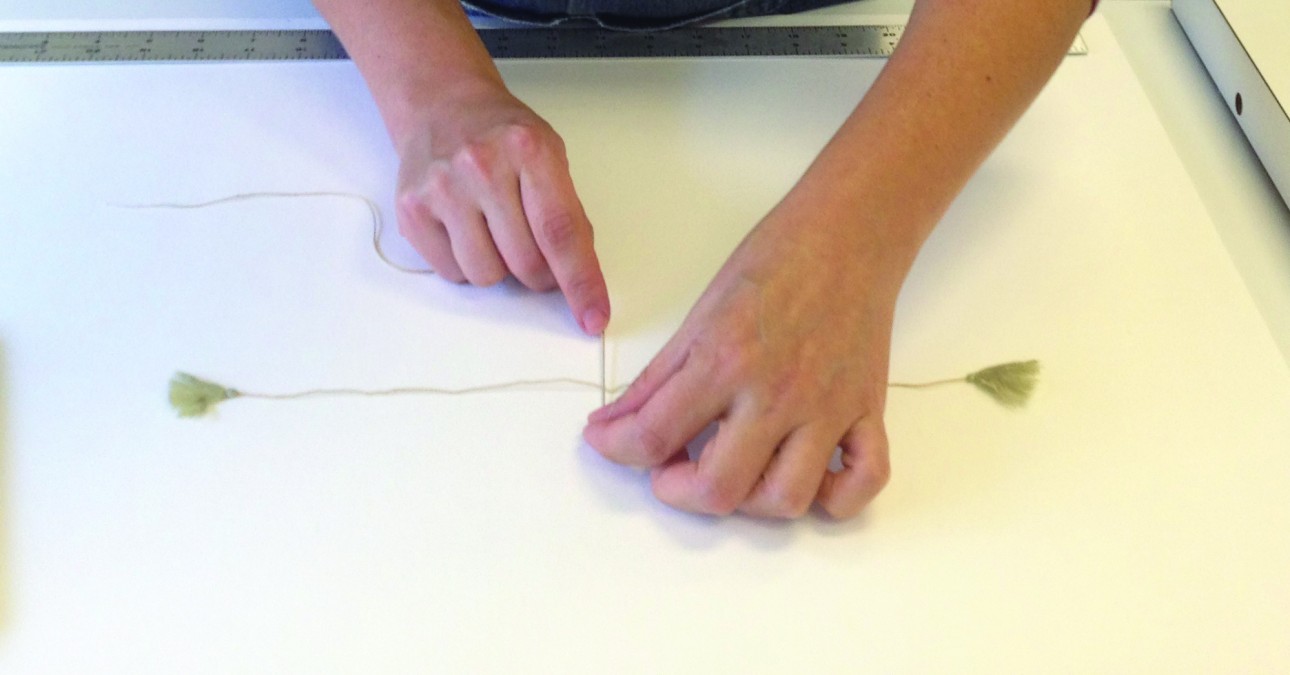

The owner of the book provided a TIFF image of the back of a different copy of A Happy Pair so that a new back cover could be made. To do this, CCAHA Manager of Digital Imaging Andrew Pinkham altered the color of the image background to match the existing cover and spine and printed it on matte paper. Godlewski then attached the new back cover to the spine with wheat starch paste. To ensure that the book could be displayed flat, Godlewski added a length of acrylic-toned embroidery thread to the original binding thread before rebinding the book.

The palimpsestic result of CCAHA’s treatment is typical of the conservation of turn-of-the-century children’s literature. The books pass through many hands, and A Happy Pair is a testament to years of children’s play, a collector’s diligence, and CCAHA’s careful conservation. Its treatment ensures that the book will be enjoyed for years to come.