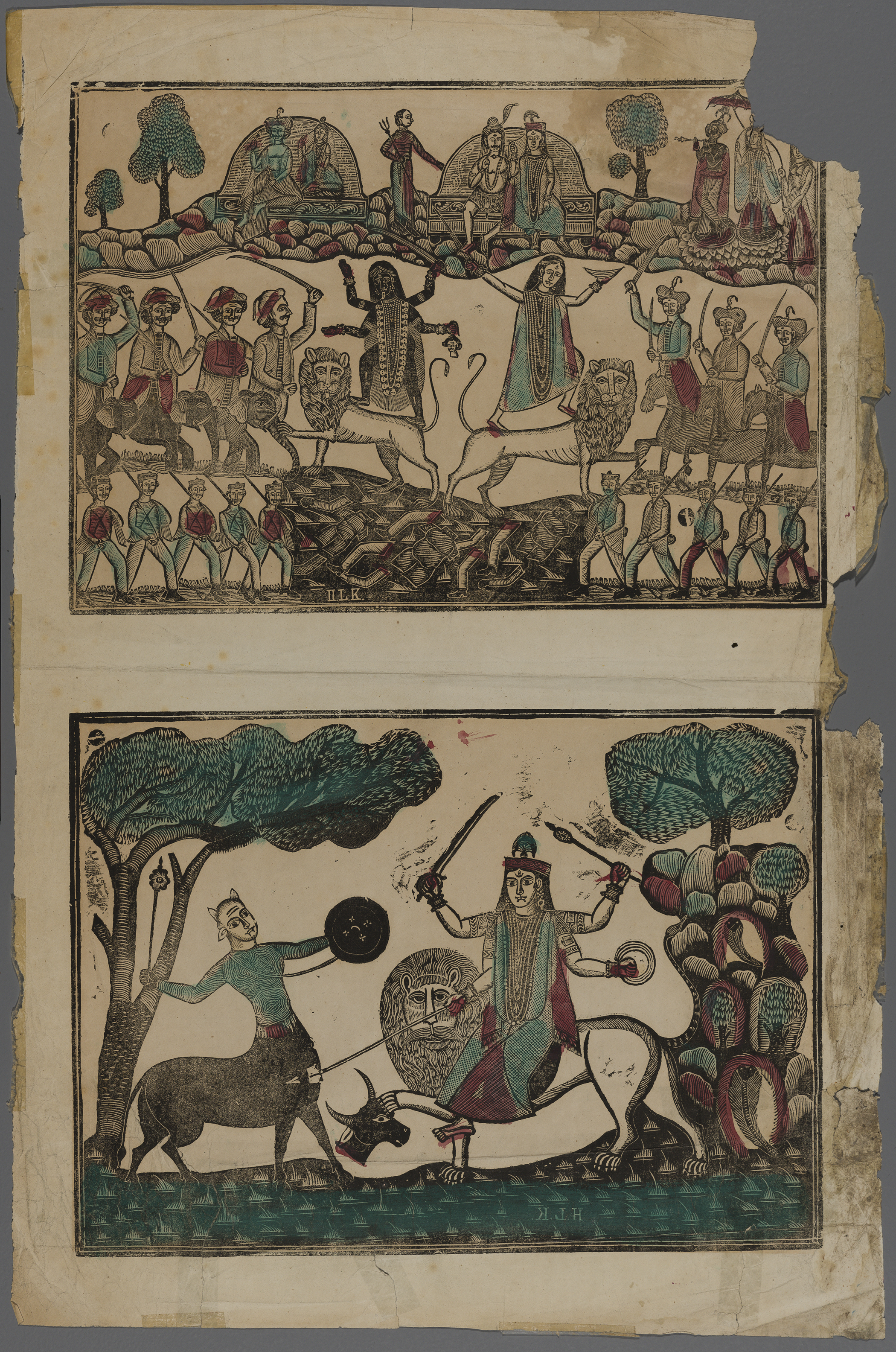

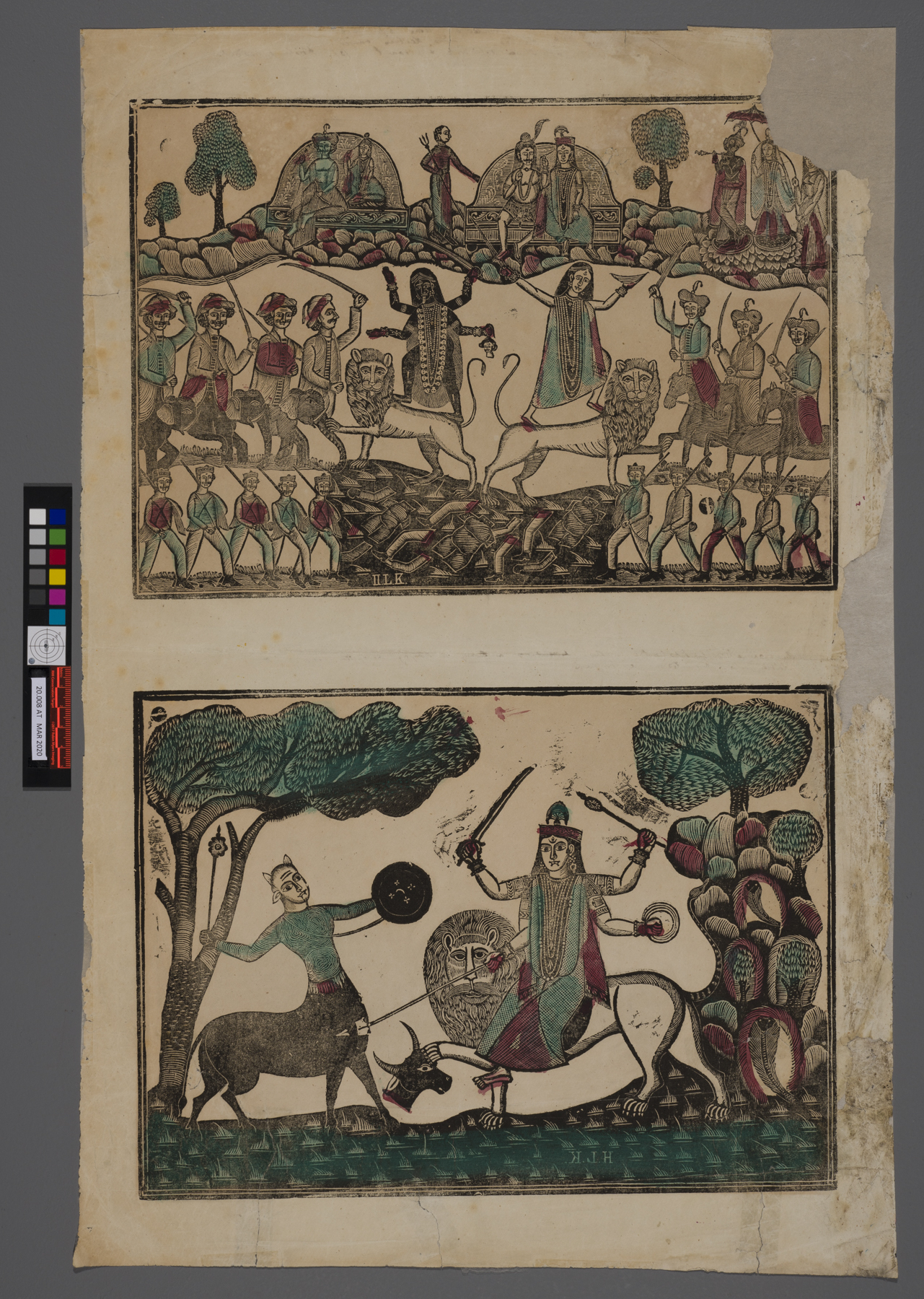

Treatment FOCUS: A 19th-century Woodcut Print of Kali & Durga

In the mid-1800s, the Northern Calcutta neighborhood of Battala was the site of a flourishing scene of engravers and printers. These artists illustrated books and produced India’s first religious prints from large-scale woodcuts of Hindu gods and goddesses, continuing a tradition that had begun at the turn of the century with hand-painted watercolors. These strikingly illustrated prints feature narrative scenes of Indian religious icons and were sought-after by both religious pilgrims and tourists.

Mark Baron and Elise Boisanté are New York-based collectors who specialize in 19th century Indian devotional artwork. Earlier this year, they contacted CCAHA to treat some damaged items from their collection of c. 1850s electrotype woodcut Battala prints. These prints were intriguing to staff, especially Senior Conservation Assistant Anna Krain, who informed staff members of the meaning of the scenes, which include the deities Shiva, Brahma, and Krishna, and feature the goddesses Kali and Durga engaged in battle.

Senior Paper Conservator Heather Hendry led the treatment. Heather explained that these prints were first carved onto wood and then electroplated with a metal facing in order to make more prints from the same block. After the metal printing plate was made, it was bolted to a support, and one of the fascinating details noticed during treatment was subtle evidence of the original screws. These would have held the plate in place and served as registration marks during the printing process.

In interviews on the subject, Baron has described the reasons that many extant copies of these prints show so much wear—factors including acidic paper and the region’s extreme humidity. When this particular print arrived at CCAHA, it had a number of cosmetic and structural issues. For Heather, the treatment involved removing large amounts of pressure sensitive tape, grime, and staining, then mending significant tears and losses. Removing over fifty inches of tape was especially difficult because of the porous, weak paper. A combination of heat, solvents, and erasers were used to separate the tape and adhesive without disturbing the paper fibers.

To fill the losses, Heather had to carefully choose the type of paper she would use. She described the print's original paper as very soft and open, typical of an Indian paper from this time. A Japanese mulberry paper, toned with acrylic, closely matched the color and weight, but the print paper was also more opaque than Japanese paper because of the short fibers and fillers used. To adjust the opacity where necessary, Heather pasted a second layer of whiter Japanese paper, the two layers together giving more depth to the color. Heather explains, “Because the Japanese paper is so strong and long-fibered, it's both the mend and the fill. This will be what stabilizes the edges as well as filling in the loss.” Throughout the center of the print, there are several small holes and gaps, which have been similarly mended with a combination of paper and remoistenable tissue. The result of the treatment is an overall improvement in the print's visual unity and structural integrity.