Treatment FOCUS: Frank Furness' Architectural Drawings

In the case of architect Frank Furness (1839-1912), one can easily see how the buildings are the product of the man. Furness has been described as hotheaded and difficult, as well as pioneering and imaginative. Critics and admirers alike have called his buildings challenging, even outrageous, but they also agree that they are daring and original.

Furness’ designs typically combined several schools of architecture. He would then add new elements inspired by the materials and forms of the American industrial age; for example, he incorporated brick, iron, chimneys, and skylights, once seen mostly in factories. The result was a unique style that found appreciation in Philadelphia, then a major industrial center, during the 1870s and 1880s. Clients felt that each Furness building—whether a factory, hospital, school, or library—transmitted an energy that complemented the work conducted within it. Furness designed more than 600 buildings, most located in the Philadelphia area, shaping the look and feel of the city.

The facade of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Starting in the 1890s, however, Victorian styles, including Furness’ work, became less popular, and many of his buildings were demolished before they came back into fashion. Today, few remain. One of the best surviving examples of Furness’ work is the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA), now a National Historic Landmark. The building features several radical design components, including exposed steel beams, gallery skylights, and an innovative passive cooling system.

From September 29 through December 30, PAFA will highlight its Historic Landmark Building in “Building a Masterpiece: Frank Furness’ Factory for Art,” an exhibition of Furness’ original architectural drawings from 1876. The show is part of a city-wide celebration of Furness that will take place this fall.

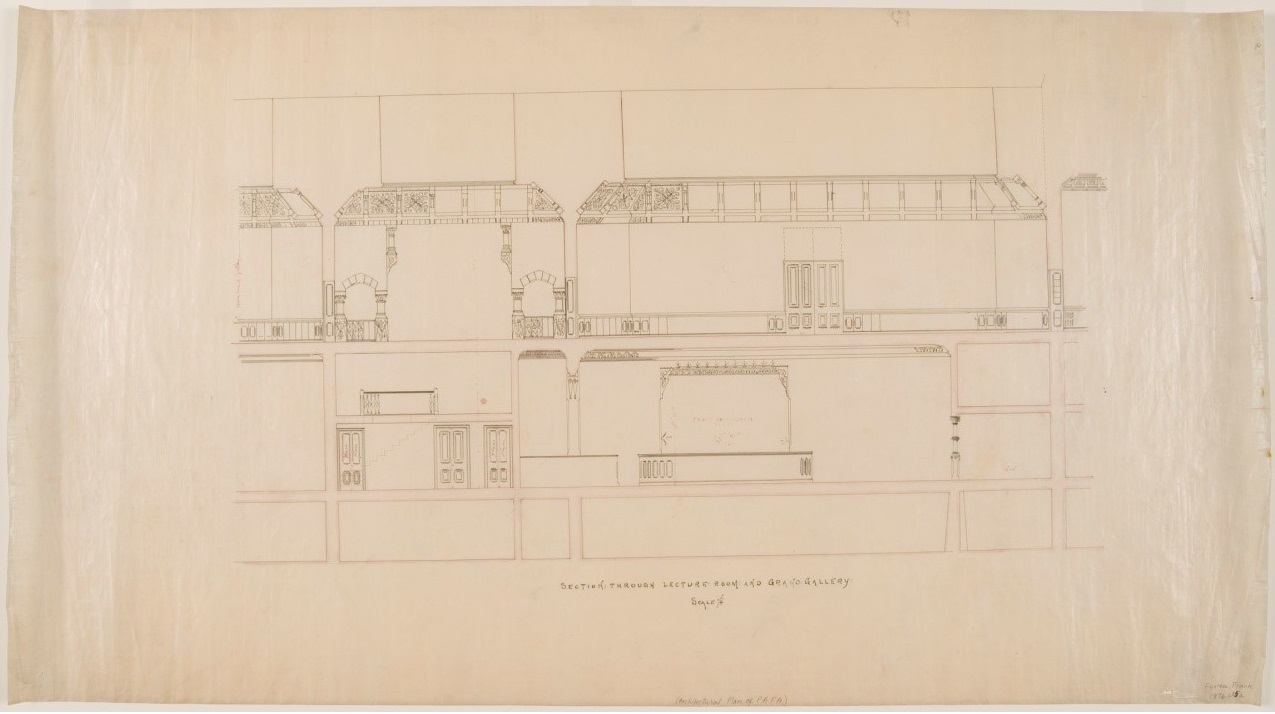

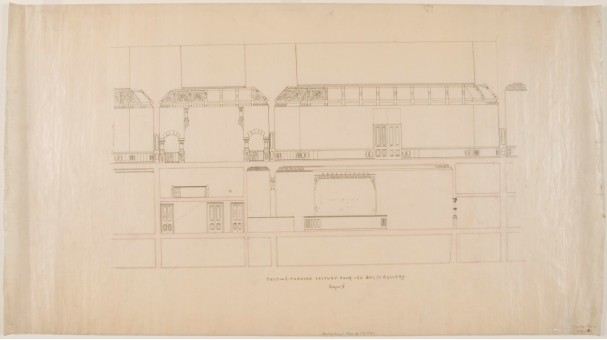

Section drawing, looking through a lecture room, after treatment

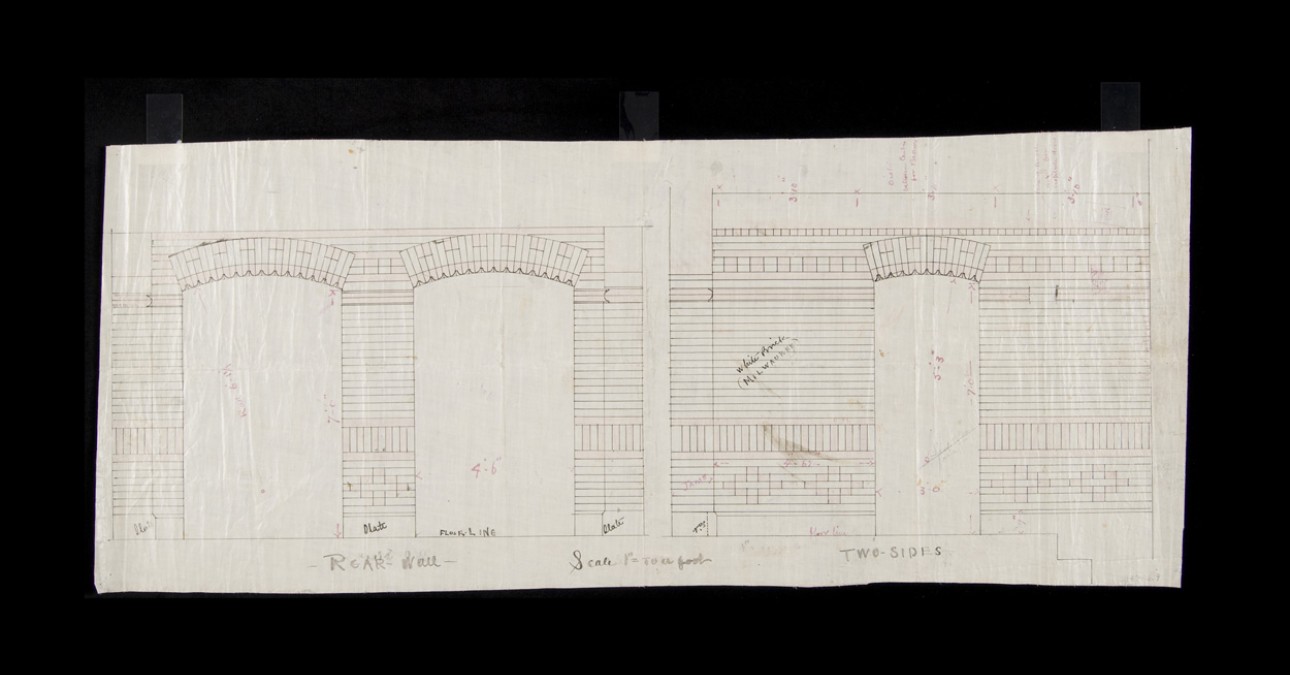

Before the drawings could go on display, however, PAFA had 14 of them conserved at CCAHA. Composed of inks and watercolors on starch-treated linen, the drawings were creased from handling and rolled storage, and many of the corners and edges had been folded. Orange and brown stains were scattered throughout, and the drawings had varying degrees of surface dirt. Due to the sensitivity of the media and starch coating to water, CCAHA proposed non-aqueous treatment only. CCAHA staff surface cleaned each drawing, removed pieces of tape with a heated spatula, relaxed folds and creases using heat, and mended tears. Each drawing was returned to PAFA encapsulated between polyester film.