Treatment FOCUS: The Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776

As the colonies prepared for a revolution in 1775, Pennsylvania faced a conflict of its own. Dissatisfaction with its conservative governing body, which had not supported any proposals for independence, had led to the formation of local “committees” that were demanding major change. In June 1776, committee representatives traveled to Philadelphia to elect delegates, including Benjamin Franklin, to draft the state’s first constitution.

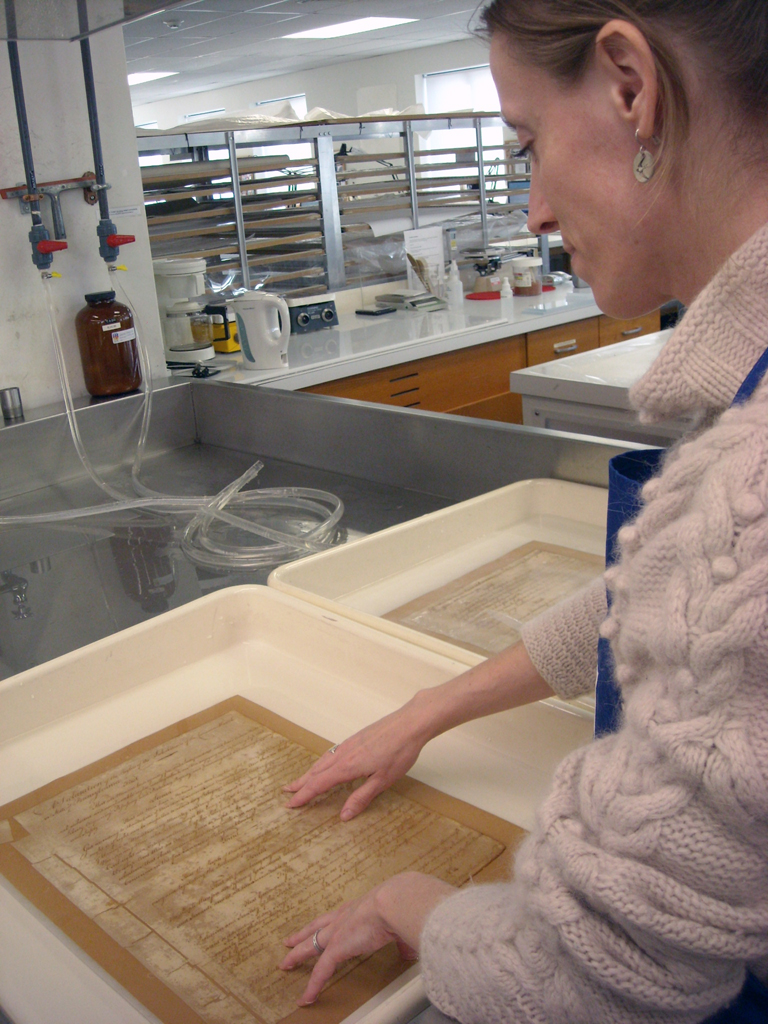

Paper Conservator Samantha Sheesley immersing a leaf of the Constitution, mounted to an album page, in a bath

The resulting document has been described as the most democratic in America. It expanded voting eligibility and listed in detail the rights of citizens. Although the Constitution of 1776 did have its problems—it established only one assembly and provided for no executive to check the house’s power—it went into effect on September 28, 1776, and elections for a new assembly took place in November.

Toning paper-pulp fills using watercolor so that they blend with the surrounding original

After the Revolutionary War, Pennsylvania adopted a new constitution that established a second legislative house and a governorship and better represented both conservative and radical groups. But the Constitution of 1776 had lasting influence, as its Declaration of Rights section has appeared almost intact in subsequent state constitutions. Today, the original manuscript can be found in the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg—although it recently returned briefly to Philadelphia for treatment at CCAHA.

Sheesley separating a leaf from an album page

When the Constitution arrived, its 17 leaves were adhered to acidic brown papers and bound in a leather album. The leaves were brittle due to prolonged contact with the acidic mounts, and they exhibited numerous tears and losses. Mends and fills from previous treatments remained. Spots, stains, and accretions were scattered throughout, and the pages displayed minor planar distortions, as well as uneven discoloration overall.

CCAHA Paper Conservators Samantha Sheesley and Corine Norman McHugh and NEA Fellow Gwenanne Edwards removed the album pages from their binding. They then reduced surface dirt that had accumulated on each leaf. After immersing the leaves in successive baths of calcium-enriched deionized water, the conservators separated them from the album pages. They removed old mends and fills and reduced adhesive residue left from the album pages. They mended tears with narrow torn strips of mulberry paper and filled losses with paper pulp. These fills were toned with watercolor to blend with the original paper. Finally, Sheesley, McHugh, and Edwards humidified the leaves and pressed them to restore planarity.