Violet Oakley’s Capitol Murals Turn 100

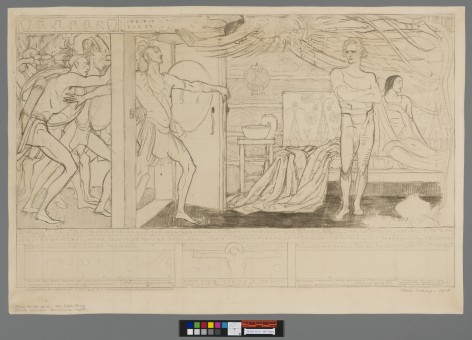

In January 1919, trailblazing artist Violet Oakley completed work on a series of three murals for the Pennsylvania State House’s Senate Chamber and Supreme Court in Harrisburg—Unity and The Creation and Preservation of the Union, The Little Sanctuary in the Wilderness, and The Slave Ship Ransomed. One hundred years later and about 100 miles away in Philadelphia, a project to conserve Oakley’s original sketches and studies for the murals was completed at CCAHA. The treatment was done in preparation for the centennial exhibit Picturing a More Perfect Union: Violet Oakley’s Mural Studies for the Pennsylvania Senate Chamber, 1911-1919, which opened at the State Museum of Pennsylvania in November 2019 and runs through April, 26, 2020.*

Though the road to commercial success was uncertain for Oakley, the path to identifying her talents was a direct one. She was born in 1874 in Jersey City, New Jersey, into an extended family that included 23 artists. Her grandfathers on both sides of the family were painters and members of the prestigious National Academy of Design. When Oakley’s family moved to New York City, her natural gifts were further developed at the Art Students League of New York, where she studied painting with James Carroll Beckwith and Irving R. Wiles.

After Violet’s father, Arthur Oakley, lost his job on Wall Street during the economic panic of 1893, his mental health rapidly declined, and he was institutionalized. The Oakley family moved to Philadelphia to seek treatment, and Violet worked as an illustrator to help earn money. In Philadelphia, she started classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA), eventually transferring to the Drexel Institute of Art, Science, and Industry (known today as Drexel University), where she studied under celebrated American illustrator Howard Pyle.

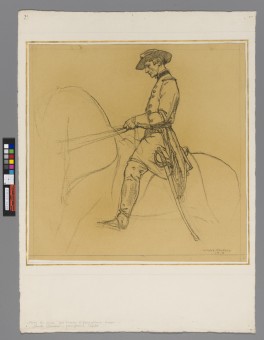

In addition to raw skill and an ability to work in a wide range of media, one of Oakley’s great strengths ensured her future—she was a gifted visual storyteller capable of presenting complex narratives. The development of these narratives began with studies of human figures and detailed sketches like those we surveyed and treated last year.

Though she was essentially an unknown, an early mural commission for a local Philadelphia church received positive reviews. In 1902, at age 28, Pennsylvania State Capitol architect Joseph Houston selected Oakley to paint a series of murals in the Governor’s Reception Room. Houston’s selection made her the first American woman to earn a major art commission, and her series, The Founding of the State of Liberty Spiritual, was completed and unveiled in 1906.

Several years passed before Oakley was invited back to Harrisburg to assist great American illustrator Edwin Austin Abbey on an assignment to paint murals in the State House, Senate Chambers, and the Supreme Court. When Abbey died in 1911, local press coverage confirms there was overwhelming public support to hand the project to Oakley. Incredibly, she labored on these murals, with their themes of liberty and justice, at a time when she was unable to legally vote. And even though she was one of the leading artists in the movement known as the American Renaissance, Oakley still contended with newspaper headlines that addressed her anonymously as the “woman artist” at work in the Capitol.

When Violet Oakley died in 1961, she left behind a vast body of work spanning eight decades, but the murals in Harrisburg remain central to her legacy.

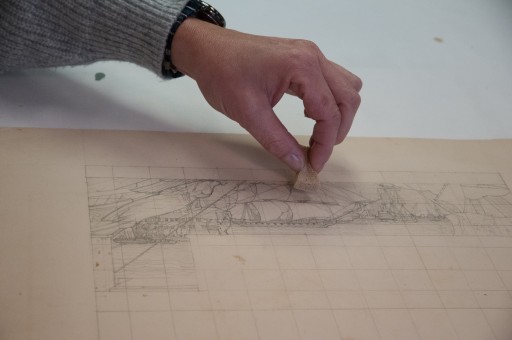

For CCAHA staff, the survey and treatment of Oakley’s mural studies was a two-phase project. The first phase consisted of an on-site survey, which was conducted May 1, 2019, by CCAHA’s Senior Paper Conservator Heather Hendry. On that trip, Heather viewed the entire collection of approximately 60 sketches in order to assess their condition and devise a treatment proposal.

“The most apparent problem was the foxing stains that occurred throughout many drawings,” Heather describes. “Most of the papers were physically in good condition because Oakley used generally good papers, but in many of them foxing either developed in the paper or was transferred from contact with less stable secondary supports. The drawings also show evidence of their use in a working studio, so there were smudges in the media and stray paint marks, and we would not want to remove that evidence of the artist’s hand.”

As Heather and other CCAHA staff members worked on the drawings, a whole host of tiny clues began to emerge from the objects—inferences about the conditions in Oakley’s studio and glimpses into her decision- making process.

“As we worked on the project, we learned from the art historian [at the State Museum] that the secondary supports with gold borders were actually applied by Violet Oakley and her studio assistant,” Heather says. “As I mentioned, many drawings had foxing that had transferred from the secondary support materials, and we would normally recommend removing them. However, in this case, the mounting was a sign that Oakley had both considered this drawing to be more than a sketch, that it stood alone as a work of art, and also that she had tried to sell it separately after the production of the murals. This made the secondary support very important evidence that we will preserve in its place, attached to the artwork, and the gold borders will be displayed within the window mats when they are framed.”

Spending so much time with Oakley’s sketches put her work in perspective for our staff, and the contrast between the rough and completed versions of these images was special to experience firsthand. The day of that first survey in May, Heather walked straight from viewing Oakley’s sketches to standing in front of some of the finished full-scale murals.

“The Senate Chamber was not open to the public that day,” Heather recalls, “but her other murals in their intended setting were incredible. Although it’s awe-inspiring to see her compositions in full color on a monumental scale, I think her drawings are even more special because you can see every line of her amazing drawing skills and really get up close to see everything she put into them.”

Above: various details of Violet Oakley's Capitol mural studies

*Update: Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, public events listed in our early 2020 edition of Art-i-facts have been canceled.