Learning in the Present to Prepare for the Future: A Greater Understanding of the Impact of COVID-19 on Collections Preservation in the United States

A report on findings from a survey conducted by Emma Ziraldo, CCAHA National Endowment for the Humanities Preventive Conservation Fellow, prepared September 2020.

What does it mean for a cultural organization to be pandemic-proof during this exceptional period? Certainly, one thing the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us is that a city without a cultural life feels dead: quiet theaters, silent museums, no gallery openings, no festivals, no concerts. Our cultural life is currently taking place at home, in a very confined space or in front of screens. It is a difficult time and the impact that COVID-19 has had on cultural institutions cannot be denied. According to the survey released by the American Alliance of Museums (AAM), the museum field has suffered substantial financial distress which may lead to permanent closures, furloughed or laid-off staff, collection deaccessions, and/or other extremely challenging outcomes. Whether the distress has been placed upon humans, objects, or both, institutions themselves might not be the same in the future.

Most museums in the United States began providing virtual education resources to maintain a connection with their communities, as has the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts (CCAHA). Webinars, online courses, Q&As, and online forums have been imperative for museum professionals during the lockdown. Furthermore, CCAHA started providing virtual preservation needs assessments for the cultural collecting institutions we serve. But how long-lasting can the shift to virtual learning and teaching be? What will the impact of this enhanced digital engagement be in the long run?

We now need to focus our attention on applying what professionals have produced in the past to the present situation. During my year-long Preventive Conservation Fellowship at CCAHA, I dedicated most of my time to providing the field with digital content: webinars for collection care in museums and historic houses, technical bulletins, policy templates, etc. Now more than ever, these resources can be useful tools for institutional staff and volunteers. Yet this “new normal” is unique: when we consider housekeeping best practices, for example, we may now think of sanitizing and disinfecting every object we touch. However, there are some things that will not change. Conservators wear gloves to conduct much of their work and personal protective equipment (PPE) are part of the essential kit that conservation labs are provided with. I suppose the attention should now go to humans more than objects. But hasn’t that always been the real reason why we do our practice? We are preserving collections for future generations to enjoy, so we need to consider that the reason for preservation is actually for us, humans, and for our education and cultural development. With that in mind, haven’t we always placed human safety before the care of objects?

Cultural institutions are not just moving toward more virtual educational content but also digitizing their collections to provide more open access. In considering this trend, my reflection goes to the conservation practice: if we move away from physical objects, should we rethink our own profession? How should we choose to approach preventive conservation?

The unexpected disruption in all services that the lockdown has created has impacted all cultural institutions’ ability to undertake preservation activities with “best practice” approaches. We should now join forces and share experiences to approach preservation solutions scalably. What can we do, as preservation professionals, today, so that we can still be relevant in the future? Downscaling our expectations from “perfect” to “good” and “better” can be a reasonable start. Perhaps we can learn from some smaller organizations that have always tried to aim at more approachable practices, balancing best practice with feasibility, due to budget constraints and other resource limitations.

It seems that perhaps the COVID-19 pandemic has slightly eased this difference and placed institutions at a more equal level, at least for the time being. To achieve a deeper understanding of the impact of the 2020 pandemic on the institutions and operations that preserve and protect our cultural heritage in the United States, I crafted and developed a survey on behalf of CCAHA.

The survey, answered throughout August 2020 by more than 180 institutions, shows that the lockdown had both a positive and negative impact on collection preservation across the country. In this new COVID world, everyday life and work are a bit slower, and so is the cultural heritage field, which actually had some positive opportunities. As Stacey Holder, Preservation and Facility Manager at the Philadelphia Magic Gardens mentioned to me, “One silver lining is that maybe the lockdown was a moment for people to assess what they were doing and how they were doing their job. Having to slow down in the last 6 months had made me rethink about the way our preservation team can operate and how much work we can handle.” Aside from realizing that the lockdown has actually been a good time to digest and evaluate what we can achieve in a more realistic way for the preservation of collections, when we consider that object hazards are partially related to human needs (think of closed museums where there is no light shining on objects or visitors walking in the galleries), we are eliminating certain agents of deterioration. For example, light damage, relative humidity (RH) and temperature levels for human comfort, or physical damage due to handling. However, at the same time a dark, closed museum can suffer from more security issues, uncontrolled dust accumulation, environments that are not monitored, or pests that thrive in undisturbed places.

Professionals responded to the CCAHA survey on behalf of their organizations, representing the cultural collecting field in the United States geographically, by size, and by type. The organizations surveyed ranged from museums, historic houses and sites, to public libraries and university collections and archives. More than 18% were history and natural history museums, with 14% representing government organizations. Historic houses and historical societies together comprised 17%, art museums 12%, while archives and collections of colleges and universities along with public and academic libraries represented less than 20%, and nonprofits with cultural collections less than 7%.

Their annual operating budgets ranged from less than $50,000 to more than $1,000,000. Most of the institutions that responded to the survey are located in Pennsylvania (25%), New York State (7%), New Jersey (6%), New Mexico (6%), Colorado (4%), and Illinois (3%). However, the survey results show a comprehensive response across the country. One institution from America Samoa and one from Alaska also completed the survey, and representatives from many other states did too. If we divide them into regions, the Northeast and Great Lakes areas comprise the majority (Fig. 1).

The survey was completed mostly by directors, board members and administrators (27%), as well as librarians and archivists (26%); collection managers and registrars made up 19%; curators 13%; and conservators, preventive conservators, preservation specialists, and conservation scientists represent 9%. It is interesting to note that 1% of respondents were volunteers.

Findings in the survey show that most of the institutions did not experience any major disasters while closed (Fig. 2). However, the 16% that faced an emergency during lockdown described issues mostly related to water hazards and moisture: increases in RH, leaking pipes, roof infiltrations, or floods due to hurricane and tropical storm seasons. Others experienced mechanical or electrical issues, mostly related to HVAC and power outages. Only one organization experienced a fire emergency and another a security problem. Unusual pest activity and mold outbreaks were also highlighted as recurring issues by organizations across the country (Fig. 3).

64% of the institutions that responded to the survey stated they have an emergency preparedness and response plan in place, but only 45 of those organizations were able to adapt their plan to the COVID-19 emergency closure. Evidently, pandemics have not been high on the list of events to plan for. The research conducted shows, therefore, that there is a strong need for institutions across the U.S. to update their emergency plans. CCAHA will keep offering workshops and the expertise of its employees to help those institutions that are working toward updating their policies and plans and training their staff.

Considering staff responsibilities during the 2020 closure, the survey shows that in most cases (22%), if not all staff was allowed on site, the director along with administrative office staff and board members were able to access the building on a consistent basis. However, in 37 institutions, access was only given to facility, security, and custodial staff who had to be in contact at all time with collection managers or conservators responsible for the preservation of not only the building but the objects as well; 32% reported that regular virtual meetings or phone calls were held weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly between facilities and collection staff. Only 5% responded that meetings were held casually as needed. We should, however, consider that only two responses of the survey were filled in by facility staff; that is, most of the staff with access to buildings and collections during the lockdown were actually not the same staff who answered the CCAHA survey. Ideally, more data should be gathered regarding inter-department communications at the surveyed organizations, and CCAHA should consider developing specific programs for this category of professionals.

Positive results show that 74% of participating institutions did not have to leave any object uncovered during lockdown, because there was enough time to at least temporarily shelter them with Tyvek or plastic sheeting. However, most of that remaining 26% that did not have the possibility of doing so stated that objects had to stay uncovered for the entire duration of the closure—up to 6 months or longer depending on their respective state or local regulations. This 26% overlaps notably with the category of organizations that do not have an emergency preparedness plan or those who, though they have a plan, could not apply it to this specific situation.

Findings from the survey (Tab. 1) also show that only 34% of the institutions took advantage of the closure to conduct thorough cleaning of the collection spaces and the building, and 38% to change or refurbish the exhibitions. Most organizations (37%) carried out deep cleaning of the galleries and exhibition spaces in relation to the new Center for Disease Control guidelines: installed sanitizing stations, disinfected surfaces and public spaces as well as added touch-less motion sensor activation systems and extra barriers, moved cases and furniture to accommodate social distancing, etc. A smaller percentage (32%) shows that the closure timeframe was also used for conducting gallery renovation projects or repairs that could have not been undertaken in such a short time if the institution was not closed to visitors. Change in exhibitions and planning for future rotations have also proven to be a good way of applying the time while in lockdown. HVAC systems maintenance, such as replacing filters and cleaning intake ducts, was carried out by 18 institutions.

Looking more closely at collection preservation issues, one of the biggest struggles resulting from the closures is environmental monitoring. 55% of survey respondents do not have remotely accessible dataloggers, therefore it was impossible for them to constantly monitor the environment until someone could access the site, which in some cases was several months (Fig. 4). However, one anonymous response said that the lockdown finally created a real reason to add wi-fi to storage spaces and purchase wi-fi-compatible data loggers.

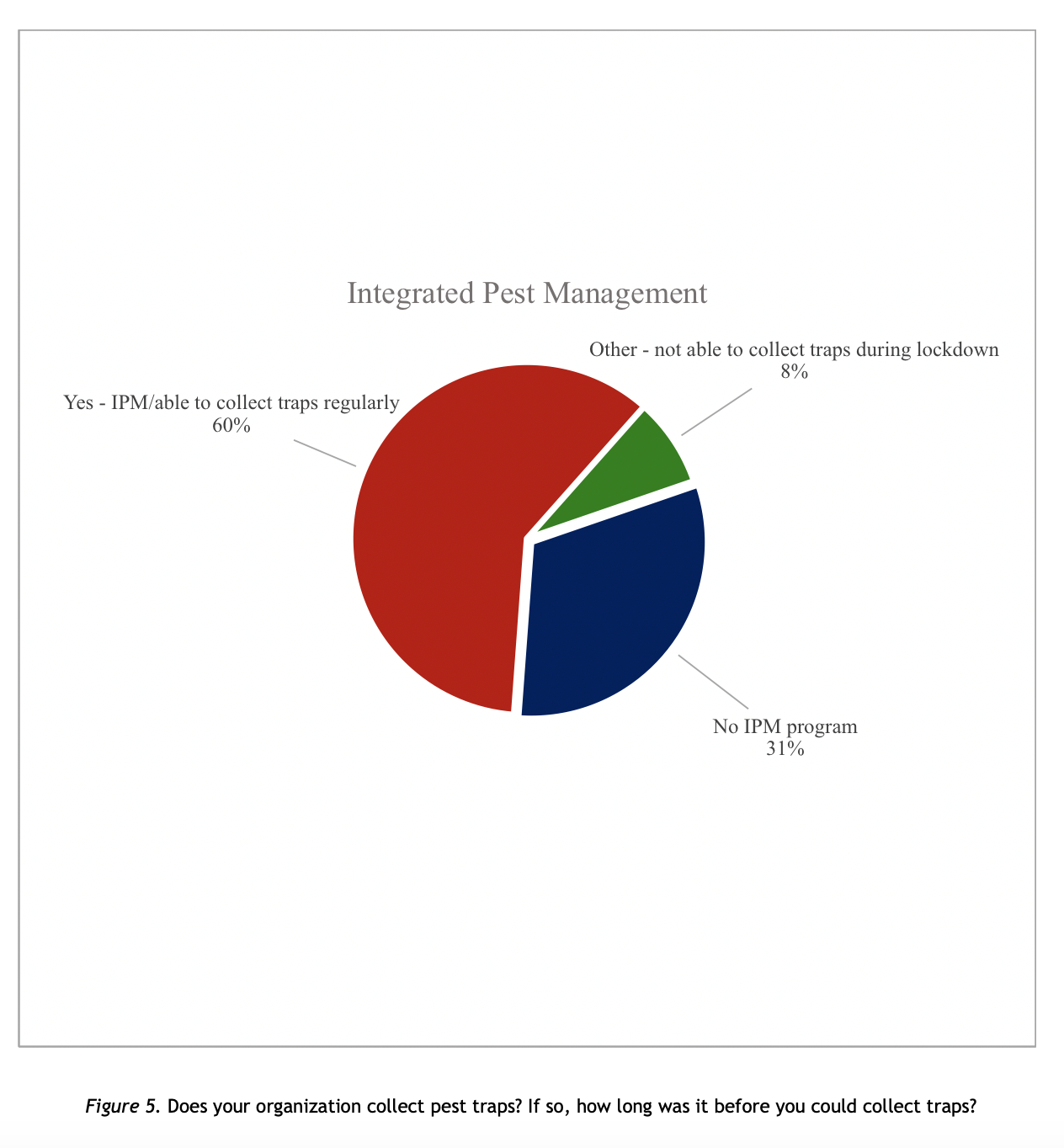

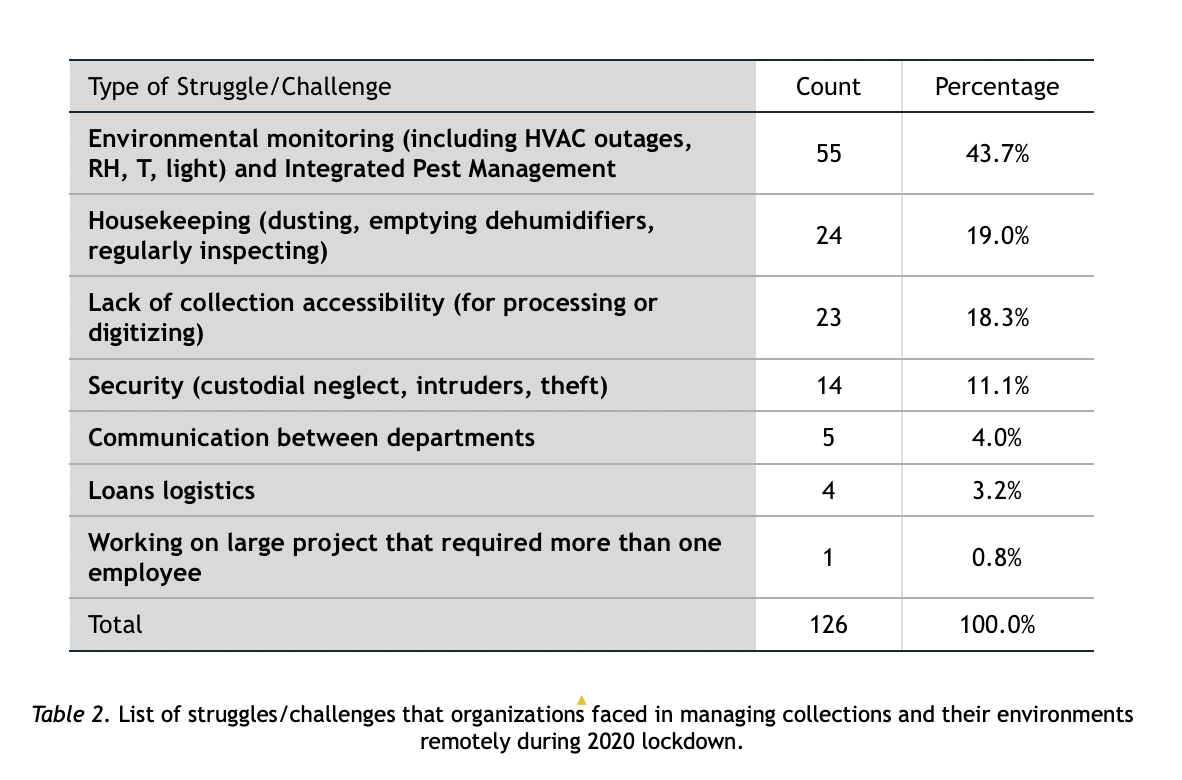

Another significant challenge for institutions (19%) has been keeping on top of housekeeping tasks in order to control dust and regularly inspecting for signs of change in materials’ conditions. On the contrary, checking on pest traps and collecting them during early spring, when pests are the most active, has apparently not been such a struggle for some institutions. The survey results (Fig. 5) show that if the organization has an Integrated Pest Management (IPM) program, then the lockdown did not make it impossible to continue replacing traps as needed, mostly because the task was already assigned to facilities staff or contractors who entered the buildings more frequently. Specifically, crosstabs survey results show that historic houses and sites, art museums and galleries, history or natural history museums, and government organizations are most likely to have IPM programs and were able to inspect and collect traps during the lockdown. However, 32% of institutions (mostly public libraries, historical societies, and nonprofits with cultural collections) do not have an active IPM program. This clearly suggests the need to implement training programs and educational activities to train collection professionals on pest identification and monitoring, since it should be an essential component of the institution’s preventive conservation program. Another anonymous response emphasizes the importance of having an IPM plan: “A webbing clothes moth outbreak was found from loan artworks in crates. They would have not been discovered if the shipment had left as planned in March. Instead, artworks were in crates from late February until July when the infestation was discovered.” In this case, the lockdown made it possible to discover an issue that otherwise could have gone unnoticed, or discovered too late when the object had already returned its collection space and the infestation could have spread to other artworks.

Regarding crates, another struggle that institutions had to face was coordinating loan logistics while not being able to access collections. The lack of collection access also created challenging situations for libraries and archives that had to suddenly stop digitizing collections and working through processing backlogs (18%). At the same time, lack of access meant the impossibility of carrying out projects with living artists. Stacey Holder shared, “The biggest struggle for us was not being able to work with the artist and not being able to bring him on site to discuss projects.”

Security issues related to custodial neglect, thefts, intruders, and vandalism emerged as concerns during the survey, however luckily these were not threats for most (Tab. 2). Furthermore, lack of communication between departments resulted in a struggle in some cases (4%). Clearly, as mentioned at the beginning of the paper and already assessed by the AAM, staffing cuts and furloughs have been a real challenge for the cultural heritage sector; this emerged from the CCAHA survey as well. 22 institutions (12%) stated that collections care staff members were included in staff cuts and/or furloughs. We should also take into consideration that most of the small organizations still survive thanks to the valuable help of interns and volunteers, for the most part, stopped collections work completely during closures. Resources will ideally need to be allocated again in the near future to support these categories of staff returning to cultural institutions.

“One advantage we had, was the lack of visitors in our museum, so we were able to work a bit more freely for longer periods of time,” wrote one employee who completed the survey. However, the same person also indicated, “But considering the COVID safety factor, certain projects are made impossible if you need to work closely with someone else.” In fact, another struggle that was addressed were the difficulties to carry out large projects that involved more than one person. Stacey Holder said, “One of the advantages was that without visitors in the space we had full range to perform routine cleaning, treatments, and repairs. Projects that usually take a long time, we were able to complete in a short amount of time because there were no visitors in the space ... Some of the disadvantages were that it was really difficult to work on projects that required more than one person because of the safety aspect.”

Given the results of this survey, we see a confirmation of how COVID-19 has impacted all cultural institutions like no situation before. Certainly, organizations need to keep working on emergency procedures, including anticipating staff illness and unexpected closures, in their plans.

If there is something this lockdown taught me personally, it is that togetherness is the key for the future of cultural collecting institutions. Mutual aid and community care should be emphasized. We must keep in mind that these past 6 months have been a unique opportunity for sharing and gathering ideas, learning from each other, and we all should embrace what we have learned moving forward. After all, even though this pandemic made us physically more alone than ever before in most of our lifetimes, it also gave us the opportunity to connect with other professionals on a deeper level in the virtual space all over the world. We keep talking about “going back to normal,” but what does “normal” even mean right now? What is the “normal” that is healthy and good for every human and every collection object? Let’s take some time to reflect and assess what kind of “normal” works for us and the collections we care so much about. Ultimately, there are so many collections across the country that have spent most of their life unseen in a storage, so perhaps this can also be a good time to rethink why and how we want to experience collections in the future.