Treatment FOCUS: Illuminated Manuscripts from Bucknell University

Long before anyone figured out how to print them, books were painstakingly produced by hand. Each manuscript passed from a parchment maker, who cleaned and stretched the cow and sheep skins that would make the pages, to a scribe. Depending on the book’s size, this process could require several herds’ worth of skins and months of work—so a manuscript often proved a costly endeavor.

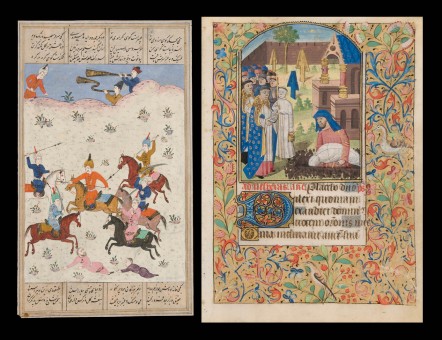

Persian miniature, 16th or 17th century, before conservation treatment / Illustration on a leaf from a French Book of Hours, c. 1460 to 1470, before treatment

Especially valued were illuminated manuscripts, which featured initial letters and illustrations in bright colors and gold leaf. Most popular in the 1400s, these handwritten texts continued to be commissioned by the wealthy even after mass-produced printed alternatives appeared. Six prime examples from Bucknell University’s Special Collections/University Archives, held within Bertrand Library, recently received treatment at the Conservation Center for Art & Historic Artifacts. All are leaves cut from books; two are 16th- or 17th-century paper Persian miniatures, produced in what is now the Middle East and South Asia, while the others, parchments c. 1450 to 1550, come from Books of Hours, small prayer books that many carried with them in France, England, and the Netherlands during the Middle Ages.

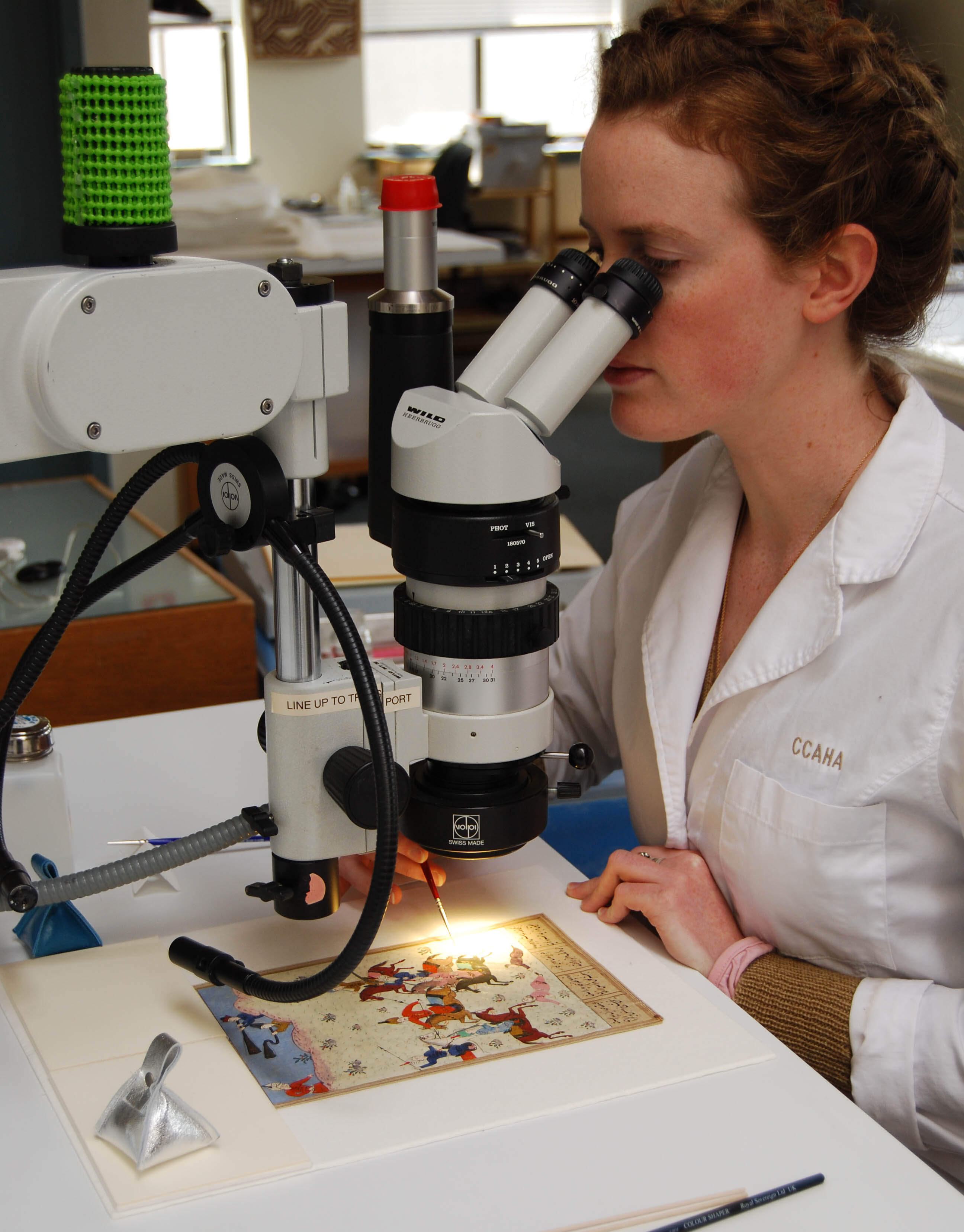

National Endowment for the Arts Fellow Marianne de Bovis looking through a microscope while consolidating flaking media on a Persian miniature

The six manuscripts shared a condition issue: unstable media. The Persian miniatures exhibited the flakiest media, as their smooth paper supports were most likely burnished with agate before the paints were applied, making it difficult for the media to grip the surface. National Endowment for the Arts Fellow Marianne de Bovis consolidated the media on each manuscript using dilute gelatin, which she applied with a thin brush while looking through a microscope. She then reduced adhesive residues on the leaves using a crepe eraser. For any manuscript with tears, de Bovis mended and reinforced the losses with mulberry tissue and dilute gelatin. She humidified and flattened several of the parchments. Then, she prepped the manuscripts for housing by attaching mulberry paper hinges, which will affix the artifacts to their housing supports.

The Library selected double-sided storage mats to house the manuscripts. The mats will allow students to view both sides of the leaves, which are heavily used in Special Collections/University Archives instructional sessions for art history and other Bucknell University classes.